BY LARRY COTÉ Special to the VOICE

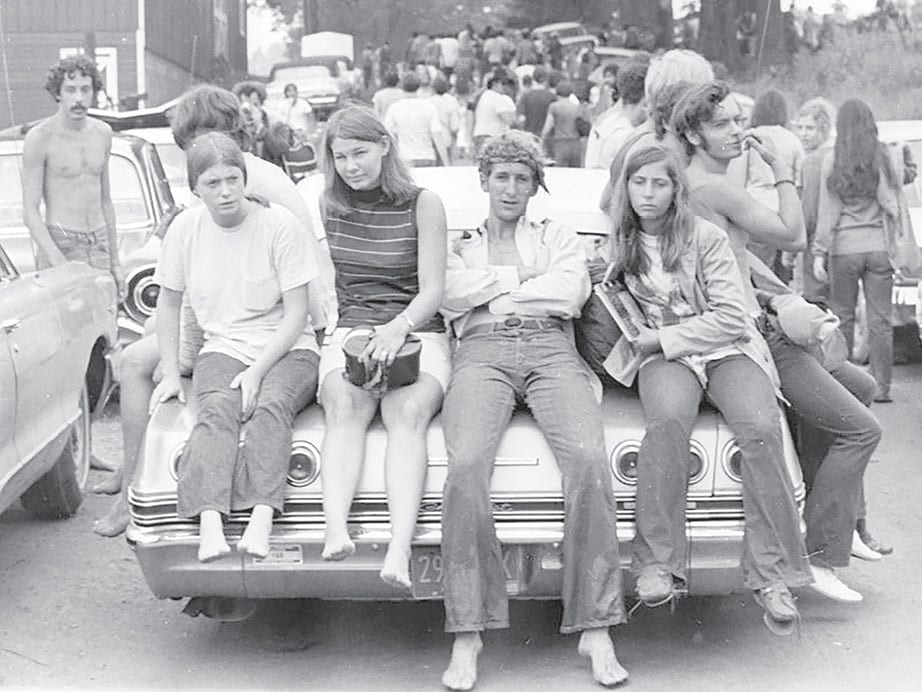

The 1967 Summer of Love was a momentous happening in some major cities in the USA and UK. Large gatherings of young people came together to protest, among other things, the politics of that time, the consumer culture, and war in Vietnam. Generally speaking the lament was they were mad as hell (at a number of things) and they weren’t going to take it anymore.

More locally, this social phenomenon was more subdued and less demonstrative than in large centers such as San Francisco, New York, and Toronto’s Yorkville. However, the phenomenon did nonetheless bring about some collateral effects among Niagara’s youth and for a very brief period.

At that time I was a college instructor and in regular contact with a large number of young people. I was a 29-year-old refugee from the world of commerce on Bay Street, and left that extremely buttoned- down conservative culture to join the more liberal laid-back universe of academia. In retrospect, it was a rather momentous leap in cultural norms, lifestyles and practices.

In 1967 I observed as some students transitioned to what I now call a quasi-hippie culture. Very few adopted the full hippie modus vivendi. Most did not become extremists but chose to adopt some of the hippie fashions, language, music and behaviors. For instance, the peace sign hand gesture was a common form of greeting, long hair became the popular style and colorful tie-dyed clothing and micro-mini skirts became favored fashions. Popularized graffiti prominently included the words, “Peace,” “Love,” “Flower Power,” and anti-war slogans. At some social gatherings there was occasionally a detectable grassy pungency in the air, but alcohol remained the most favored mind-altering substance. LSD was the popular recreational drug within the mainstream hippie movement and fervently promoted by Timothy O’Leary, a favored icon of that time. However, in my experience, this psychedelic was not widely available nor used locally.

Being a reasonably young person and constantly in the company of young students, the onset of these new norms also affected me in some ways. I ditched my pin-striped suit for the more popular style of those times. My new attire include a suit jacket with lapels wider that the wingspan of a 747, and bell bottomed trousers that would put a naval recruit to shame. My previous buzz-cut hairstyle gave way to shoulder-length tresses with mutton chop sideburns and my calico framed glasses were replace by circular lenses in wire frames. My three bedroom brick bungalow became a “pad” and I “dug” the lingo, brother.

As a more academic observation, I admired the fact that large numbers of young people came together, like never before, in a collective effort to right what they perceived to be wrongs in our society. For the most part, they did this peacefully and without rancor. After all is said and done, it is difficult to object to a collaborative that had as its motto “love” and “peace” and advocated for “flower power.” As the peace-loving group they professed to be, they were worthy of being called “the beautiful people.”

The phenomenon of the Summer of Love in 1967 was rather brief in duration and by the fall of that year much of its momentum and intensity had dissipated for most of its followers. For most it was a memorable time in their lives and they soon returned to mainstream society. Many returned to immerse themselves in their studies and soon shed the vestiges of being a hippie. There were some who choose to stay in the moment of the movement and became, and remained, die-hard hippies.

On this, the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love it might be appropriate to turn up the amplifier and listen to the anthem of that time made famous by Scott McKenzie, “Be Sure To Wear A Flower In Your Hair.” Or if you prefer to be your more conventional self, crank up the old phonograph player and listen to, “I Lost My Heart in San Francisco” by the ever-crooning Tony Bennett. Same city, same sentiments.

Whatever your choice… Peace.

Larry Coté is a retired college professor. He was awarded a Governor General’s Medal for his community activities.

What were you doing during the summer of ‘67? Write it up and send it in: [email protected]