BY COLIN BRZEZICKI Special to the VOICE

Everything comes at a price, though not with a lifetime warranty.

“Progress has never been a bargain,” says Henry Drummond in the famous Monkey Trial case from Inherit the Wind. “Mister, you may conquer the air, but the birds will lose their wonder, and the clouds will smell of gasoline.”

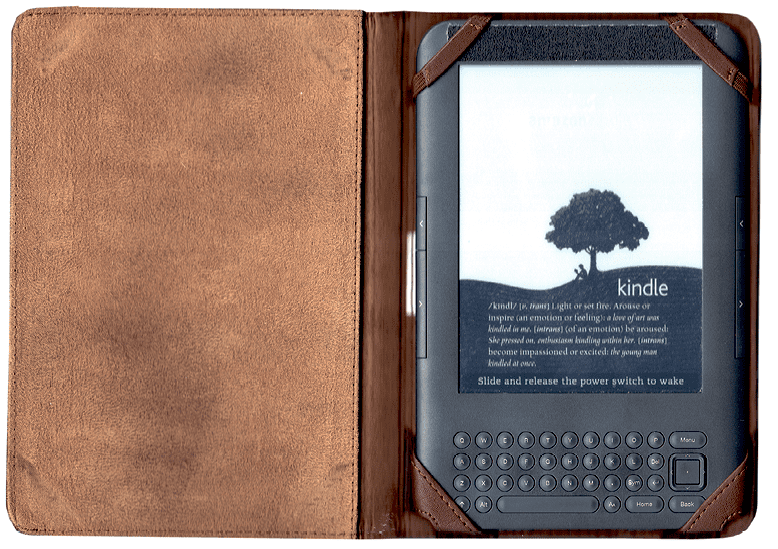

A decade ago I introduced my English class to a revolutionary device that was invented to replace the book. I passed the e-reader around the room, having downloaded The Mayor of Casterbridge, and asked the students to take a turn reading from the device.

One girl looked at it, stroked the unresponsive screen, then stared at me. “So, what else does it do?”

It’s a question Amazon has been answering ever since, releasing successive new version of the Kindle. Today, it provides not only the requisite touch screen, but other applications and features that bring the device ever closer to the physical book it set out to replace.

Now, when you turn the screen page it actually curls back from the top just like a real one. A rustling sound effect would complete the illusion.

In other ways the e-book surpasses the real thing, with an “audible” option that reads the book to you, a rechargeable battery, and backlighting. Its storage capacity, equal to that of a small library, makes it especially convenient in an era of decluttering.

Back in 2008, my students weren’t all that enamoured of the prototype, being accustomed to reading fiction from a book. “I see the words, but I’m not actually reading them,” one student remarked. Another said, “I just finished reading a page and now I can’t remember any of it.”

All that has changed in 10 years. The screen is now the medium of choice in many schools, with “choice” not really an option any more.

Given all the improvements—you can now fall asleep while reading a waterproof Kindle in the bath or by the pool—it’s surprising the e-reader hasn’t cut more drastically into the sale of books. Mega-sales of the likes of Harry Potter, Fifty Shades of Grey and Dan Brown, have helped to keep books afloat in an electronic age. And some people still prefer the physicality of print; they enjoy the feel of the pages, the smell, that sort of thing.

Though one could argue that the e-reader’s sleek casing and empowering touch controls make it sexier than ever. Nicholas Carr tells us in Utopia Is Creepy (2016) that a “captivating interface is the perfect consumer good,” that it “packages the very act of consumption as a product.”

Whatever the reason, e-books continue to make headway. Recent figures reported by The Daily Telegraph indicate that e-book purchases rose to 64 million in 2014 from 57 million in the same period a year earlier; now, with iPads and other interactive tablets offering even more sophisticated alternatives to books, the trend can only continue.

But does it matter how people read? If readers are reading, why should we care if it’s from a book, an e-reader, a tablet or phone. It’s all in the reading, right?

Maybe not.

What exactly do we mean by reading in the first place? Are we scanning the text or processing it? There’s a big difference.

An article in the World Economic Forum (October, 2017) reports that an overwhelming percentage of university students prefer to read from a screen, read faster from a screen, finish assignments in a shorter time, and come away with a general understanding of the material. But their grasp of critical detail is significantly poorer than those who read the same text from a book or printed article and take longer to do it.

Speed reduces comprehension and retention. Nothing new there. I think of the proverbial speed-reader of old who finished War and Peace in an hour and said the book was about Russia.

I read differently online than I do the printed page. And if I’ve spent hours reading off a screen, I have to force myself to slow down and concentrate when I pick up a book again. If I want to follow the contours of a sentence, catch the ambiguities and ironies of language use, take time to hear the writer’s voice and listen to what isn’t being said, along with what is, I have to slow down.

Joseph Epstein, who knows a thing or two about writing, having taught literature at the University of Chicago for four decades, remarked that the point of writing is not communication: Pandas, lions, seagulls, after all, communicate—nor is it information, of which the world already has enough. The point is engagement: intellectual, emotional, imaginative, even spiritual.

If I’m reading a work of fiction I must give my imagination time to settle on an evocative sentence, so I can conjure a setting, or a face, hear inflections in the dialogue. The fiction and memoir writing I enjoy most is the kind that makes me do the work.

A novelist, David Bezmozgis, compares the relationship between reader and writer with that of weightlifter and spotter—the reader gets the workout, while the writer only gives a hand when needed.

For that kind of reading we need an undistracted space around us to echo the writer’s voice:

Caught in the dark cathedral

Of your skull, your voice heard

By an internal ear informed by internal abstracts

And what you know by feeling,

Having felt.

(Thomas Lux)

To hear that voice, and take time to unspool its narrative thread, we must occupy a deeper, undistracted stillness.

How will a generation of children do all that, when reading on a tablet must compete with all the other things they do on a tablet? Or is the future of reading already mapped out by the multi-award-winning Nosy Crow, with its clamorous midway of bells and whistles, musical feed and animated illustrations, pop-out words and live links to avatar worlds? A recent count showed that Nosy Crow’s mobile apps have been downloaded 130 billion times.

I can only admire the technological acumen, the digital second nature (or maybe now first nature) that child consumers will acquire by immersing themselves in books that do all the heavy lifting. I can foresee these young readers one day encountering a physical book, only to swipe their fingers across its pages and demand to know, “What else does it do?”

I ‘m reminded of an Isaac Azimov story (likely not available on Nosy Crow) called “The Fun They Had.” It was written for a children’s magazine in 1951 and envisioned schooling in the year 2157. Lessons in Azimov’s futuristic world take place at home with a “mechanical teacher,” programmed precisely for the individual student’s ability, and returning digitally evaluated homework without ever actually seeing the student. The plot turns on the discovery of an old book in a dusty attic, an object that fascinates children who had never heard of a book. They suppose it must have been fun for children a long time ago to be able to read a book, to be able to do it all themselves.

Asimov wrote his story from a sadly obsolete viewpoint, for he believed there is nothing more interactive than a book. Now, electronic interactivity is what learning’s all about. That, and speed, unending distraction, fun, and the extinction of boredom. Whoever said learning is hard work didn’t realize it can be as easy as point and click, swipe and touch.

The single drawback to high-end, waterproof e-readers is their price tag. But, remembering Henry Drummond’s caveat, everything comes at a cost. And while it would be silly to deny that online reading will continue unrestrained, with devices delivering information and distraction more quickly and comprehensively than ever before, I wonder if it will cost us a precious commodity we won’t even miss.

Just as the industrial revolution initiated what many believe is costing us our planet, the technological revolution might lead to the extinction of our literary imaginations.

But the literary imagination will be an easy price to pay if we don’t miss it. And who knows, maybe it will evolve into something better—like clinical reality. If a finger swipe can conjure a genie to make our every wish its command, then what’s left to do but sit back and enjoy the ride?

If this is what we always imagined an ideal world would be like, well, now we don’t even have to imagine it.

And maybe that’s just as well. In any case, we’ve no choice now but to be patient—not a trending virtue, but still—and see if there’s anything we’d like to have back.