School board caution over a classic may not be a bad thing

BY COLIN BREZICKI Special to the VOICE

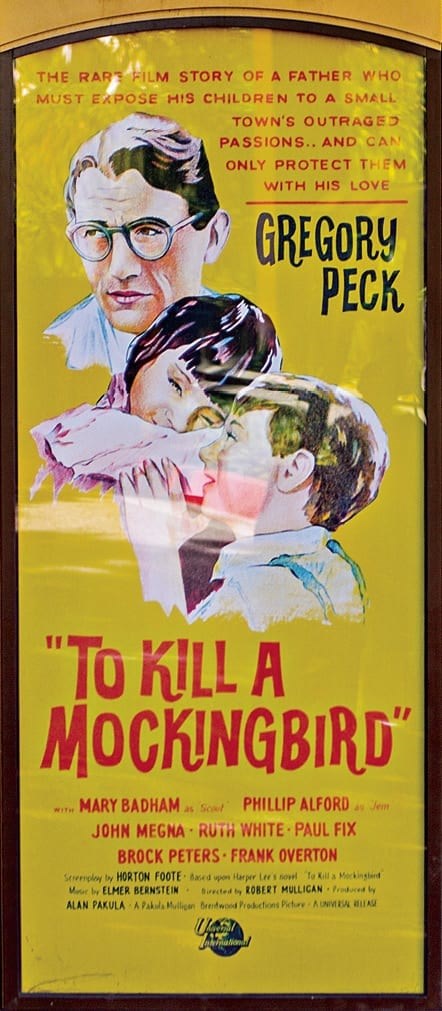

In the same week that Peel Board of Education placed To Kill A Mockingbird on its endangered species list, Americans overwhelmingly chose the book as their best-loved novel of all time. The apparent contradiction merits something more than a Tweet.

A hue and cry has risen over Peel Board’s directive. It hasn’t actually banned the book, but is advising teachers that they teach it at their own risk. Should a parent of a black student—or any student, really—take issue with this book on the syllabus, the board will leave it to teachers to defend their choice.

Inevitably, the spectre of another literary classic, Orwell’s 1984, is raised by rights activists defending the freedom to teach all great books, and even not so great books, as one wishes. They believe that Peel Board is taking a giant step down the wrong path, one that will lead to the dystopian society of Fahrenheit 451 (the temperature at which books spontaneously combust).

A sidebar here. Technology skeptics have suggested that our addiction to the internet through a myriad of electronic devices has all but eliminated books, especially ones that don’t have any pictures and take too long to read. But of course, that’s just silly.

The real threat to books, it’s claimed, are education boards. Nothing new there, of course. As far back as the late ‘50s, Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye was banned from public schools in Toronto. I still managed to find a copy and read it, and then I became an English teacher so I could share it, and books like it, with other generations of kids. And I never had a problem explaining to any dubious parents what the book had to offer.

I taught To Kill a Mockingbird for many years to Grade 10 classes that just happened to be all white. The novel challenged them on several levels: its language and complex narrative require focused reading; its moral spectrum is nuanced (even the racists are mostly hard-working, church-going, law-abiding citizens); and its underlying premise, that we can never understand someone without walking around in their shoes for a time, lies at the heart of all great fiction. Finally, it exposed my students to the stinking, festering carcass of racial hatred. If it made some of them uncomfortable, well, that was a good thing.

It’s hardly surprising that the novel is now the darling of, I would guess, mostly white people of “privilege,” in the same way that Sidney Poitier was once embraced as the black actor who took on compliant roles that made tolerant people feel good about themselves.

I suspect that To Kill a Mockingbird addresses the same need in readers who believe in equality as long as it happens on their terms.

But I wouldn’t teach this book today because now it makes me uncomfortable, for very different reasons.

I could never again read out the n-word if it was included in a chosen passage, and I'd feel for any student who had to quote that passage to support an idea. I couldn't presume now to celebrate the heroism of Atticus Finch in taking on the white supremacists of Maycomb County, albeit in a losing cause, because today it's unthinkable that any decent lawyer wouldn't.

And in the end, Harper Lee looks after her own. The white Finches return to their privileged lives, and the black Robinsons to their broken ones, in what seemed to satisfy their author as a comfortable resolution.

Today, with a black student in my class, someone whose family might still be in the cross-hairs of racial hatred, I would feel a fraud, a teacher with nothing to tell that student that he hadn’t already lived. Instead, I'd re-read Laurence Hill and Austin Clarke, and absorb what I didn't know before trying to share it with a class.

Mind you, I might be ticketed for cultural appropriation by the more virtuous, teaching black literature, but I believe I could handle that one.

I was once challenged by a parent for teaching Inherit the Wind, a play about the famous Monkey Trial in Tennessee in the early ‘20s. Staying very close to the facts of the case and its historical context, the play puts the creationism and science at loggerheads. The creationists, playing with a stacked deck, win the day, but the play mocks the proceedings of the kangaroo court while awarding the moral victory (and all the best lines) to the evolutionist lawyer, Henry Drummond (aka Clarence Darrow).

One boy in the class was made uncomfortable enough to go home and tell his parents that the play confused him. They were an orthodox family and believed in the Bible as the literal word of their Christian God. Why was I teaching this heresy, they demanded to know.

I would have liked for the boy to share his concerns with me first, but it was too late for that now. I asked his parents if they had read the play. No, they hadn’t, but their son had told them that it made fun of those who believe God made the world in six days.

Actually, I said, the play only makes fun of those who would shame and even imprison people for not believing it. That’s something different altogether.

Doesn’t matter, they said, it’s confusing our son and we don’t want him in your class while you’re teaching this book.

I tried to explain that the play did not discredit the Bible in the way that the creationists demonized evolution. That really the intent of the play was to defend the fundamental right of people to think for themselves, to consider opposing viewpoints—like creationism and evolution—and determine their own position. I hoped they would see for themselves that maybe this was something they were denying their son, but they didn’t.

Instead they quoted me a line the boy had given them, when the lawyer, Drummond, declares that he doesn’t believe in right and wrong. What kind of book teaches that immoral thinking, they asked.

I explained that the lawyer was only saying that notions of right and wrong can change overnight. That it was once right for black people to sit at the back of a bus, and not use white-only bathrooms or drink from white-only water fountains or attend white-only schools, but now that’s wrong. What Drummond believes in is truth that doesn’t change with the times.

I would have quoted Martin Luther King (himself quoting nineteenth century abolitionist, Theodore Parker) that "the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards truth," and that we’ll never get there if we don’t examine both sides of an argument to find the truth somewhere in between. I wanted also to mention that Inherit the Wind was actually written in the early ‘50s as an attack on McCarthyism, another movement that sought to suppress free thought.

But, sadly, they didn’t hang around long enough for me to explain these things, and I duly gave their son a different book to read.

But there are no two sides to racial hatred. It has only one side and, unlike many students, I’ve never been a victim of it. I can teach a play that encourages us to think for ourselves, but what do I have to say about a novel whose message, while self-explanatory, doesn’t go far enough or cut deeply enough in our day?

I don’t mean the book should be banned. I don’t know of any book that should be banned. Even Mein Kampf shouldn’t be banned. It’s almost become required reading now, given the changes going on in our political climate, though I would hesitate to teach it to a class with Jewish students in it.

I would suggest that for all its dashed hopes and good intentions To Kill A Mockingbird was always a comfort zone, and now a celebrated one, a safe place to withdraw to when we need to reassure ourselves that we are good and decent human beings, certainly not racist thank you very much, and wasn’t it an outrage that Atticus didn’t win. But that’s Confederates for you.

I don’t believe the book should be banned, only that it’s passed its shelf life.

Peel Board is not telling teachers to avoid Mockingbird; it’s simply alerting them to a truth—that times have changed and the book now comes with added “baggage,” especially in a multi-racial classroom. What was once a comfort zone for well-meaning teachers has become a minefield that they should traverse at their own risk.

I expect that any teacher who wants a student to know how to think rather than what to think, would choose texts that facilitated rather than impeded this objective.

To that end, I believe teachers’ own “rights” are superseded by their “responsibilities” to their students. If no one takes responsibility for another’s rights then no one has the right to anything. Our right to cross safely at a green light is entirely dependent on others’ responsibility to stop at a red one.

I’d give To Kill a Mockingbird, if not a red light, at the very least a red flag.

Exactly what Peel Board is doing. ♦