Readers note decline in winter bird population, reaffirming five-decade North American trend

Over the past few winters, one of the consolations of gazing out of our patio windows on gloomy afternoons has been the activity of songbirds, eagerly pecking away at a variety of seeds and nuts we have stocked in our backyard feeders. But their numbers seem to have been dwindling this season, as evidenced by reader comment to the Voice.

This perception is buttressed by research published last fall in Science magazine, which documented how bird populations have plummeted in the past five decades, dropping by nearly three billion across North America (an overall decline of 29 percent from 1970).

Ken Rosenberg, a collaborator on the research project and a senior scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, in Ithaca, NY, told Science that the collateral effects of the decline are profound.

“We’re talking about pest control, pollination and seed dispersal,” he said, referring to the roles birds play in ecosystems.

Because it is relatively easy to monitor birds, their presence or absence in a habitat can be a useful indicator of other environmental trends. Essentially, if the birds are hurting, we can be pretty sure that other parts of the ecosystem are also in degradation. Sickly birds were an early warning sign of the environmental damage caused by the pesticide DDT, a generation ago.

Grassland-dwelling birds such as field swallows and meadowlarks have been hit especially hard. According to the Science study, more than 700 million birds across 31 species that make their homes in fields and farmlands have vanished since 1970. Rosenberg says the most likely explanation involves changing agricultural practices (which removes nesting habitat) and use of pesticides (which kills insects that birds rely on for food).

Closer to home, birders Bob Highcock and Jean Hampson, of the Peninsula Field Naturalists, who serve as compilers for the St. Catharines Christmas Bird Count (CBC), echo the concern. “Looking at the reports we have received, the number of species observed for many of the southern Ontario Christmas Bird Counts have been lower than average,” Highcock told the Voice. “The St. Catharines CBC last December indicated that the number of species was near the average of the previous 12 counts, but the total number of individuals [birds] was below average.”

Marcie Jacklin is a Niagara resident and internationally recognized authority on birds. She was the lead science librarian at Brock University for 25 years (now retired) and has been a member of Brock’s Environmental Sustainability Research Centre since 2011. With some two and half decades of experience bird watching in the Niagara area, Jacklin has participated in multiple counts, including Christmas Bird Counts, Breeding Bird Surveys, and Marsh Bird Monitoring Surveys.

“Birds are definitely on the decline, and although birders have been aware of this for many years, others who have feeders or are active in the outdoors are just beginning to see this loss now,” she told the Voice.

Jacklin attributes the decline of songbirds to two factors: human disturbance and habitat loss.

“Birds that cannot adapt to living with humans are losing numbers. Invasive species like house sparrows and starlings seem to be thriving, but we are seeing fewer chickadees, field swallows, swifts, American goldfinches, and junkos. And pesticides kill insects, so birds that eat insects are dying off.”

In Niagara, habitat loss is connected directly to wetlands, woodlands and grasslands which are being destroyed. The loss of native trees alone in Niagara in the last decade has been enormous, asserted Jacklin.

“In Niagara we have lost most of our wetlands. Ponds are not wetlands. Wetlands are highly productive ecological areas which have taken thousands of years to develop and can’t be easily recreated by humans.”

She offers a solution.

“A Natural Heritage System should be developed and protected as soon as possible at the regional level. This should be based on scientific and expert data.”

Natural Heritage Systems are networks of interconnected natural features and areas such as wetlands, woodlands, lakes and rivers. They help conserve biological diversity, maintain ecological functions such as movement corridors for wildlife, and sustain ecosystem services such as pollination and clean water on which we all depend.

Not all birds are in decline locally. Robins appear to be present in significant numbers, drawn to the orchards and vineyards which have made Niagara famous. And, due to climate change, many birds are no longer migrating south.

Bill and Kim Duffin, who work a 100-acre fruit farm in Pelham, are resigned to the fact that birds will cut a swath through their crop each year.

“The first of July, you’ll hear my [propane-powered] bangers,” said Bill, “in an effort to scare off the robins, starlings, and blue jays that invade my trees to feast on my five acres of sweet cherries.”

Duffin also noted that he regularly sees owls and hawks in his orchard —usually around dusk —which prey on the hundreds of squirrels which call his farm home.

And let’s not forget about crows, which appear to be thriving in Niagara. There is nothing subtle about these intelligent birds. They are loud, especially before sunrise. As social birds, they flock together, all the more so in winter.

Neonicotinoids, a class of insecticides, were in the news in 2014 for their harmful effects to bees and other pollinators. It turns out that these chemicals may also be impacting songbird populations. A 2017 study by researchers at the University of Saskatchewan and York University found negative effects on small birds from imidacloprid, one of the commonly used neonicotinoids.

These insecticides are applied to almost all corn and canola seeds in Canada, and coat many soybean seeds as well. Tens of millions of acres are involved. They are widely used on crops in the US as well, although the EU banned neonicotinoids in 2018 because of the harm to pollinators. Health Canada is proposing to phase out agricultural use of these insecticides, but is still evaluating data prior to issuing a decision.

In the Saskatchewan/York study, wild sparrows were captured at a southern Ontario stopover during spring migration, and were fed doses of seeds coated with neonicotinoids. Tracking devices were attached to the birds. The study suggested that the insecticide suppressed the birds’ appetite leaving them comparatively lethargic. Their migration was delayed by a few days while they regained weight. The days lost in migration might well mean losing a chance to breed, both in timing, and in energy levels after arrival at breeding grounds.

“These chemicals are having a strong impact on songbirds,” the study quotes Margaret Eng, a post-doctoral fellow and one of the study’s researchers at the University of Saskatchewan. “We are seeing substantial weight loss and the birds’ migratory orientation being significantly altered by neonicotinoids. The affected birds ate less food, and it’s likely that they delayed their flight because they needed more time to recover and regain their fuel stores.”

Christy Morrissey, a toxicologist and senior author of the study, stressed that migration is a critical period for birds, and timing matters.

“Any delays can seriously hinder their success in finding mates and nesting,” said Morrissey, “so this [study] may help explain, in part, why migrant and farmland bird species are declining so dramatically worldwide.”

Another substance of concern is mercury. Recent findings from Western University in London support the scientific opinion that mercury is one of the determining factors for the dramatic declines of many migratory songbird populations across North America.

In a 2018 study published in the Journal of Avian Biology, Western biology researchers concluded that migratory songbirds with higher levels of mercury in their bodies were less likely to return from their migrations to southerly wintering locations. They determined this after examining mercury concentrations in tail feathers of migratory songbirds sampled at the Long Point Bird Observatory in southern Ontario.

The study quotes Yanju Ma, senior researcher: “We are convinced that in some bird species, elevated mercury levels impact these birds’ neurology in a way that affects their ability to manage the challenging journey to their wintering grounds thousands of kilometres to the south.”

Other perils for songbirds? Millions fall victim to high-rise buildings, flying into large, reflective glass window panels. Light pollution is also a concern. A little-known fact is that songbirds migrate at night. Distracted by light, the birds can potentially become trapped or thrown off course. Finally, cats. Not the musical. House cats. Feral cats. They kill millions of birds annually. Cats are natural hunters, and songbirds are easy prey. To help mitigate these losses, several European and North American locales have instituted various feline birth control measures. One such effort is N-SNAP, the Niagara Spay Neuter Assistance Program, based in Fonthill.

What can be done to help our Pelham songbirds? Here is a short list of a few small things that can have a big impact.

• Make your backyard bird-friendly. Plant native trees and shrubs, especially types that produce fruit.

• Reduce window collisions around your home. Make your windows less reflective by adding black plastic silhouettes. Relocate feeders to areas further away from windows.

• Provide birdhouses around your property so that songbirds will take advantage of them. Stock them with quality seeds.

• Keep your cat indoors. Or at least put a bell on it.

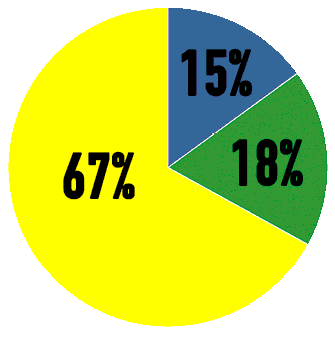

THE VOICE POLL Where did all the birds go?

In anticipation of this story's publication, last weekend the Voice ran a snap survey through our website and Facebook, soliciting reader opinion as to whether they were seeing MORE, ABOUT THE SAME, or FEWER songbirds at their feeders this winter, with responses separated geographically by Fonthill, Fenwick, and Elsewhere in Pelham. Overall, some two-thirds of respondents reported seeing fewer birds this year. The largest drop was seen in Fonthill, where fewer birds were seen by nearly 2.5 times more readers than those reporting about the same or more birds.

Overall, 15% of all readers reported seeing more birds, 18% reported seeing about the same, and 67% reported seeing fewer birds. 39 readers voted.

ADVISORY: While safeguards are in place to eliminate multiple votes, this is a self-selected poll, meaning it has no scientific validity compared to a formal random survey undertaken by a professional polling firm.