An unthinkable month of cruising, and lessons learned

We were doing it as the trip of a lifetime,” said Tim Wright of Fonthill, without a hint of irony. He was referring to the cruise he and his wife Karen took this March and April on the MS Zaandam. They would be sailing around South America, departing Buenos Aires for the Falkland Islands, then navigating the Beagle Channel and Straits of Magellan before returning north along the remote shores of Chile, traversing the Panama Canal, and concluding in Fort Lauderdale 31 days later.

You may know Wright as a recent volunteer Chair of the Pelham Library Board, a Rotarian, or as a member of various community associations. Professionally, he was President and CEO of the Welland County General Hospital, VP of Regional Operations at the Niagara Health System, and Executive Director of the Niagara Peninsula Children’s Centre.

The following is his account of what happened as COVID-19 engulfed the Zaandam, and some of the many lessons learned.

“We didn’t take the decision lightly, we thought seriously,” said Wright. “We talked about what the chances were of there being problems.” The Wrights had booked their trip nine months earlier.

“As the cruise got closer and other cruise ships became in the news, notably the Diamond Princess and Westerdam, certainly we started thinking—do we still want to do this, do we want to back out, what would the consequences be?”

Holland America offered no options other than to lose everything, which for this 31-day cruise was a substantial amount of money.

Wright realized that if just one infected person boarded the ship there was the potential for trouble, so he studied all the available information in late February and early March, and did the math.

“They were talking 20 to 40 COVID cases in all of the United States.”

Since the number reported at that time for Canada was slightly higher, Wright suspected the US number was inaccurate, and estimated it was probably more like 1000 or 2000.

He then figured, “What are the chances of one of those people getting on the ship?”

Wright’s research suggested there were 150 cruise ships circulating in the world, averaging trips of two weeks’ duration. During the most recent 300 trips, only three ships experienced trouble, so in his mind the chance of a problem was a one in one hundred, or one percent.

Wright also saw that in all of South America there was only one reported case of COVID-19, concluding, “We were cruising to a part of the world where it was not an issue. We decided to go.”

In response to comments made to or about them as the Zaandam’s plight was reported in the press, Wright responded, “It was a wrong decision, but I don’t think it was a stupid decision. I don’t think anybody in the world, if they’re being honest in their mind, anticipated the amount of change that was going to happen in the world between March 7th and April 1st. We didn’t have any thoughts of something like that in our mind.”I don’t think anybody in the world, if they’re being honest in their mind, anticipated the amount of change that was going to happen in the world between March 7th and April 1st.

After spending a night onboard in Buenos Aires, day two was a short cruise to Montevideo, Uruguay. Next were the Falkland Islands, where Wright speculated how interesting it would be to spend time in such an isolated place. He and Karen enjoyed a beautiful first five or six days of cruising.

The Zaandam next docked in Punta Arenas, Chile, at the southern tip of South America.

“This is when all hell started to break loose.”

While moored, the captain notified guests that their next port-of-call, Ushuaia, on the southern tip of Argentina, was closing.

The captain decided to sail south toward Ushuaia to view Cape Horn and the spectacular channels, knowing there would be no dockage. During that night’s cruise to the Ushuaia area, the captain received word that Chile was also going to close their ports the next day.

Understanding that Punta Arenas had a small airport from which passengers could have been flown home, the captain reversed course in an attempt to reach Punta Arenas while their port was still open. Chile arbitrarily advanced their deadline by eight hours, ensuring the Zaandam did not arrive in time.

The ship stayed at anchor in Punta Arenas for two days while negotiating permission for the passengers to depart from the local airport. Holland America, the ship’s owner, managed to arrange flights, but ultimately Chile would not let the ship dock. The captain was forced to sail north along the west coast of Chile, searching for a port with access to a larger airport that would allow the Zaandam to dock.

The five days spent sailing north to Santiago’s port city, Valparaiso, didn’t disrupt the cruise much.

“That part of the cruise was a little happy-go-lucky. People were disappointed they didn’t get to see some ports and sights, but we had access to entertainment, food, bars. People were lightheartedly saying that in reality we were likely in one of the safest places on earth. At this time we’re assuming the cruise is clean. In Punta Arenas, there was no word from anyone of any illness on the ship.”

The March 20 and 21 stop in Valparaiso was an anchorage for fuel and supplies only, Chilean authorities would not allow dockage or passengers to leave the ship.

During this portion of the trip, Tim and Karen both endured mild illness, but recovered. Wright recalled the experience.

“That night I felt lethargic with chills and flushing. I thought I should report this. The next morning, I went to sick bay.” Wright searched for descriptive words, eliminating “shambles” and “mess,” settling upon, “It was extremely busy. There was a ton of people down in sick bay. I was probably the healthiest person.”

“I had to wait, there was a long lineup of people, and they took my temperature. My temperature was normal, and by that time I felt fine. I was told that I wasn’t sick, and that I could go. Sort of a ****-off, we got more important things to do.”

Leaving Valparaiso, Tim and Karen had just finished a Trivia game with 50 other passengers when the captain’s voice was heard throughout the ship. “Go directly to your cabin, do not delay, stay in your cabin until further notice.”“Within 20 minutes to half an hour, the ship was abandoned,” says Wright. “Some time later the captain came on again and said that there was a lot of illness on the ship, sick bay was very busy, and for everyone’s protection he ordered us to stay in our cabins until further notice.”

The Wrights were in quarantine.

“We did not hear again for four days. No other word on the seriousness of things. We had no idea of the magnitude.”

Wright’s understanding was that the ship would then pass through the Panama Canal headed to Fort Lauderdale, the original embarkation point, and that the MS Rotterdam was on its way from Acapulco to assist with medical supplies and personnel.

“Life in isolation is horrendous,” stated Wright matter-of-factly, recalling the leg from Valparaiso to Fort Lauderdale.

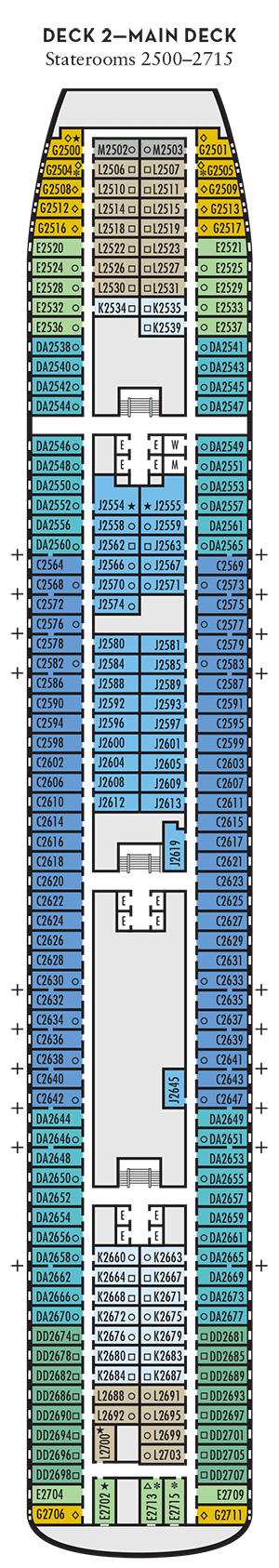

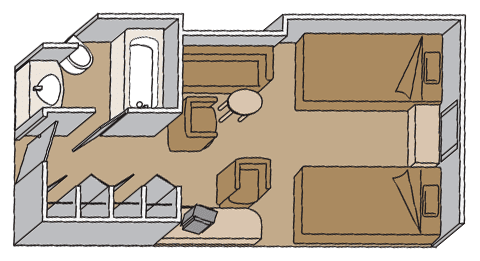

“The cabins are small. You have a king bed, a narrow strip down each side to get in and out of bed, a small sitting area and a small washroom. That’s your world. You’re under quarantine, you couldn’t step out into the hall, meals were delivered to your door. There was a knock on the door, the person disappeared, and you pulled your tray in from the hallway. You ate and put the tray out. That was the highlight of every day. Three meals. The [in-cabin] entertainment package is notoriously bad on cruise ships. We had Fox and MSNBC, two garbage news channels, the Food Channel, a channel about the off-ship excursions you could take, and a music channel. So you had lousy entertainment, three meals a day, and your bed to sleep on. That was quarantine life. We got clean towels every second day, we put our garbage outside and it was taken away. There was no housekeeping in the rooms, and no clean sheets. The ventilation is a central system, sometimes it seemed to work, sometimes not. There was a question in our mind as to how healthy it was.”

Wright said that it took four days to reach the Panama Canal.

“As we got closer to population centres, and hopefully some help, our mood brightened. We’re sailing into Panama Harbour, seeing other ships, feeling a bit better, and the captain comes on and gives an update of our situation.”

Wright said the news shocked him and his wife.

“Four people had died, there were 80 people ill—40 passengers and 40 crew—with basically undefined, flu-like symptoms.”

Passengers learned there were no testing kits on board, and that the captain was awaiting word on passage through the Panama Canal. Morale totally deflated.

Wright noted that by this time CBC had picked up on the Zaandam story, and he wondered if the captain would have announced anything if their situation wasn’t becoming public knowledge.

A positive thing the captain did early into lockdown was provide every cabin with WiFi for communication—a lifesaver for Tim and Karen. Karen began writing emails to about 35 friends, and they Facetimed with their daughter twice a day, getting and giving support.

While the Zaandam waited for clearance in Panama, some 800 healthy people chosen from the 1800 on board were transferred to the Rotterdam, including Tim and Karen. During the first night on the Rotterdam, Wright’s flushness and fever returned. He reported it to sick bay by phone, and was provided an in-cabin consultation. The medics then put him and Karen in isolation, which is a step more severe than quarantine. Two days on the Rotterdam, and they were both on the sick list.

Although the Rotterdam was allowed through the Panama Canal, they learned via internet news media that Florida didn’t want them. The passengers were surprised, as they had expected American ports to be more welcoming. On Thursday April 2, they finally docked at Port Everglades, Fort Lauderdale.

A communication nightmare ensued. Despite many calls to the front desk, the Wrights were provided no information, and had no understanding of their status.

Friday they learned that relief flights to Canada had been arranged.

“We kept seeing suitcases appearing in the hall, then being carted away, and we didn’t get any information as to be ready. We got no information at all. All we knew was we weren’t being included in this.”

They later learned that this was because of their illness status.

It was about this time that the Canadian consulate in Miami contacted the couple, providing support. On Saturday Tim was declared off isolation, but Karen was not put on “Santa’s good list” until Sunday, April 5. This was vitally important, because they heard there was another flight leaving Sunday.

They fought hard to get on that flight, but the consulate, their only link to what was really happening on the ship, kept replying, “You’re not on the list, you’re not on the list.”

Wright informed the consulate that they we’re cleared to fly, but they came back each time telling them they were not on the list.

What they learned later was that Karen had in fact been added to the flight list—after the plane had taken off. Wright despaired, “Something in the internal communications between the doctors or infirmary and guest services was such a slow process that we did not get on the flight.” This was the second opportunity to leave that they had missed.

To make matters worse, the Wrights had been re-positioned to an upper balcony cabin, so they watched as busloads of fellow-Canadians disembarked while they were left behind.

The Wrights knew there were very few people left on the ship by the number of meal trays being delivered, maybe three or four in the whole hallway. They still had no communication from the ship, or Holland America’s Head Office in Seattle, which had taken command.

On Monday morning, April 6, the captain informed those few remaining on the ship that the Rotterdam would be leaving port that evening, yet the Wrights had heard nothing of their fate.

Wright said that at this point his mood was very down and depressed.

“There was no information, no idea if they’d come up with a solution or not. I’d heard so many times from the front desk that they’re working on it, ‘We’ll get back to you’—you don’t believe anything you hear.”There was no information, no idea if they’d come up with a solution or not

Late on that exasperating Monday, the captain came back on the PA and informed those remaining that the ship would stay docked in Port Everglades one more day.

Finally, Tuesday morning, April 7, the notorious front desk called Wright, and asked if they were packed. Wright replied they had been packed for five days. Front desk told them to be ready to leave in two hours.

Tim and Karen were glad of the news, but wouldn’t believe it until they were off the ship. They waited three hours without word, searching for a bus to appear dockside. It never came.

At 2:15 PM, the couple were assisted off the Rotterdam. There was still no bus, but the Wrights were directed to a pair of limousines. Nine other Canadians disembarked with them, the last of the 250 that had been on the Rotterdam when it docked five days earlier. Four or five Canadians remained in Fort Lauderdale hospital.

Once off the ship, Wright said the arrangements made by Holland American were excellent. They were driven to a far corner of the Miami airport tarmac, separated from the public and never near the terminal. The 11 Canadians shared a plane north with approximately 100 Americans released from the similarly distressed Coral Princess, in Miami. The flight stopped at Atlanta, Charlotte, and Washington DC, deplaning passengers on distant runways with accelerated protocols every time.

From Washington, destination for the final American passengers, the 11 Canadians flew via a small executive jet back to Toronto. Public Health officials entered the plane upon arrival in Toronto, taking temperatures and questioning everyone. Upon clearance, each person was given a COVID-19 kit with instructions to be followed during mandatory isolation. Canada Customs did a quick check of passports, then Karen and Tim were driven to their door in Fonthill via minibus.

Public Health Canada called the couple twice a day during self-isolation, checking on their status and asking questions about symptoms. The Wrights had to take their temperature every morning and late afternoon, and provide the results to Health Canada.

Wright said with a smile, “We passed with flying colours. We’re back, we’re healthy, and just as bored as everyone else now.”

But there were lessons learned and thoughts to share about cruising and travel in the future.

“If there’s any hint of a problem, do research.”

Wright wishes he’d done more. He’s just now learning via recent studies not available pre-cruise, that when statistics in early March claimed 20 people sick and one dead from COVID-19 in the US, there were in fact probably 30,000 people infected.

For Wright, this more accurate information would have changed his calculation, and there is “no way” he and Karen would have taken the cruise.

As an aside, Wright shared that on the morning of departure from Buenos Aires, after all passengers had spent the previous night on board the ship in preparation for sailing, one woman felt so uncomfortable she abandoned the boat.

“In hindsight,” says Wright, “she’s the smartest woman I know.”

Wright said that it was important to register with Global Affairs Canada, and use the Canadian Consulate.

“When things started going badly, we registered with Global Affairs Canada, and I would urge everyone to do so if they start getting into a situation like this. Through this whole thing, the consulate was extremely supportive of us. I must have talked to my contact there, a very pleasant lady, a dozen times while we were stuck in Florida.”

Wright stressed travelers should recognize that the consulate provides moral support, and can argue your case for you, but they have absolutely no power. Everything is up to the host country.

“It’s very worthwhile to include them, but don’t expect them to solve your problems.”

Wright added that it’s important to understand the additional risks travelling in remote areas entails.

“One thing that struck me later about the period when we were sailing up the west coast of Chile is how remote that area is. There is absolutely nothing down there. It’s really an isolated part of the world.”

Wright warns how these areas present accessibility challenges, and avoiding such destinations will influence his next trip.

He cannot imagine the risks that would have ensued had all the Zaandam’s passengers been allowed to fly out of Punta Arenas. Twelve hundred people travelling for five or more days, staying in hotels and passing through airports with no knowledge of their health status.

Don’t expect normal communications during a crisis, said Wright.

“The communication on the ship was terrible. The captain made one announcement, then disappeared for four days. The only communication passengers have is by telephone. You couldn’t go into the hallway, walk to guest services, any of these things. You had to call guest services, and their refrain each and every time was, ‘We’re working on it, we’re looking into it, and we’ll get back to you.’ No one ever got back to you. I was worried about my mild illness and wanted to ask some questions, but you were never able to get beyond guest services.”The communication on the ship was terrible. The captain made one announcement, then disappeared for four days.

Plus, Wright said, there were no counselling services that he could find for those that might be in a special situation.

Wright believes the stress of losing control had the worst negative effect on him. Towards the end of the ordeal, he began having nightmares, which continued for a few days after returning home. He was willing to share this during the interview only to emphasize the following point.

“My message to people thinking of travelling, especially on cruise ships, or even in general, is that when you’re travelling overseas, you’re basically there at the will of the governments where you are. You can go quickly from having the rights of a traveler to having no rights, and very little recourse to do anything about it. It was amazing how quickly the captain put us in lockdown. It became very militaristic. I went from a citizen of good standing, able to do pretty much what I wanted to do, to an individual who had no rights at all. I didn’t have access to any of the authorities on the ship, any of the authorities in the countries we visited, those that at that point had control over my life. This is a huge warning to people that once you fall into that part of the system, you’re very easily controlled, then lost in the system. People don’t seem to care about you, and you have no control over anything in your life.”

Where are the Wrights going next?

Tim responds quickly, vowing that they will not stop travelling. He does admit that he and Karen have different opinions about whether they might cruise again though.

Wright believes the cruise industry will take a tremendous hit, but says others share the blame.

“My biggest disappointment in this is the reactions of the various governments in the world. The cruise industry has had pitches from so many countries, ‘Come here, come here, we want you here.’”

Wright is referring to the economic benefits derived when a cruise ship docks.

“It was a very severe disappointment that at the first sign of trouble, the abandonment by that other partner in the process [the country being visited] was total, as was the betrayal of passengers that wanted to see their country.”

“People are seeing the precariousness of travel, and what can happen. The travelling public must have in mind what will happen if they do get in crisis, and ensure that the travel companies they choose and their partners have these types of emergency systems set up.”

Lastly, the Wrights want to thank everyone in the community that supported them. The well-wishes, they said, and knowledge people were thinking of them, made a tremendous difference to their morale and gave them a warm sense that they were cared about. ◆