FICTION

Faith

By Eveline van Berkum

High up in the Alps of Switzerland was the little wooden hut where Francois lived, like so many other boys in Switzerland. But the little brown structure which was Francois' home was different from other Swiss homes in that it was smaller and had a poorer appearance. Francois lived there with his mother's sister and her husband. He had neither father nor mother. He remembered distinctly the story he had been told of his mother's life and his own childhood. She had been kitchen-maid in the splendid palace of the Bourbon kings in France, the palace of Louis XV, the Bien Aime. She fell in love with a young man who was engaged in dusting the bed chamber of the very king himself—an exalted position, and they were married with the gracious consent of His Majesty himself.

For one short year they lived in happiness and then a son was born to them, Francois. That was in 1773. Another year of happiness ensued. Both parents remained in the palace and they were still there when suddenly his Majesty was taken ill with the smallpox, that very serious and dreaded disease which often resulted in death. Such was the case this time. His Majesty died, deserted by the majority of his relations, servants and friends. But a few remained. Among these was Francois' father, who to the last day carefully dusted his Majesty's bedroom. But the disease was extremely contagious, and on the day after his Majesty's death, the servant was taken ill. After a week of struggle, he also joined his Majesty in spite of his wife's patient nursing, and Francois was was left a fatherless child. But more misfortunes seized the widowed woman. A new king was about to ascend the throne and he issued a proclamation that all those who had been in the presence of the late king or who had been near a person sick with the disfiguring disease, should leave Versailles before a certain date. That meant Francois' mother! She had always been an obedient subject and realized the necessity of the measure. Imagine if the beautiful queen should ever fall ill—she was too lovely to go to Heaven yet!

But what was the widowed woman to do? She had no relatives in France and no one would take care of her since she would no doubt harbour the germs of smallpox. Long she thought one night, and suddenly it flashed on her tear-clouded memory that she had a sister in Switzerland. The sister was a compassionate woman and would certainly let her work to earn the daily bread for her son and herself. But how was she to get there? She concluded that she must walk. Perhaps some kind peasant along the road with a cart would give her and her charge a ride as far as he went.

One morning she set out, her darling in her arms, with what money and valuables were left to her cast in a bag on her shoulder. With tears in her eyes she took a last look at the domains of the dynasty she had served so faithfully. She realized how much she had respected his Majesty, who owned all France, who had so many nobles pay court to him, who made all the laws, who spent so much money for feasts in the palace, which she helped to prepare and taste of—yes, his Majesty must be very powerful for he could do exactly as he pleased.

She suffered great privation, and a long time after she had left Versailles she reached the foothills of the Alps. Far away she saw the snowy peaks and thought of days of hardship, cold, hunger and fatigue that were still in store for her and her child before she should reach her destination. Five days later she realized that she was becoming ill. She suffered from the cold, her feet were wet, her child was so heavy and food was scarce, for there were not many houses bordering her path. Still she struggled forward, with courage never daunted by the frozen formidable heights above her. Yet every day she felt weaker, and when she had at last reached the higher level, she knew that she could not live long. However, she inquired and found out that she was not far from her sister's home. One afternoon she caught sight of it, but distances in the mountains are deceiving, her steps were slow and tiresome, and she only reached it after dusk. Her child had suffered very little during the perilous trip, but now she knew that her mission was fulfilled and her strength ended. With a dull thud she fell against the door of the cottage; her child, wrapped in cloths and shawls, fell into the snow. Bright shone the stars and full was the moon—the heavens could not have provided a more gentle setting for the death of an ancient Greek hero.

The child began to cry, for though not a gust of wind blew, the atmosphere was bitterly cold. The people inside, alarmed, came out and found the woman and her child. Soon she was recognized, and also the child, for it bore a striking resemblance to the mother. The situation was shortly made clear with the aid of the local clergyman who read the document that the woman had caused to be written some days previous by another clergyman, explaining all. The childless couple took the child into their simple home, cared for him and were rewarded by a sturdy, good-looking boy, in spite of the fact that they were very poor.

When he was sixteen, he was given the last wishes of his mother regarding himself, through the mouth of the same clergyman who had been present at his mother's funeral. He was told the story of his parents and how he came to Switzerland, and also his mother's last wishes, which urged him to seek employment in the service of the French king, whoever he might be at that time, and to think always of France as his native land. Moved to tears, the boy had pledged his faith and left for the little brown building that he considered his home.

For two years now his only playmate and friend had been the girl from the nearest house some distance down on the same mountain. This was pretty Adele, her mother's only child. She had a sweet disposition, but yet she was a little spoiled and haughty. She had no father—he had died while rescuing a lonely traveller from an avalanche years before—and her mother was a well-to-do lady, who lived with her people, Adele's grandparents, who further spoiled the only child. But Adele was not without her good qualities—she was generous, intelligent, witty, unafraid of the dangers hidden in the mountains surrounding her. Adele loved the outdoors and spent long hours in tramping up the mountains and picking the gay flowers that covered the slopes in the summer, and sliding down the paths in the winter. She herded the few cattle, her grandmother's pride, but she loved animals and this was no tedious task.

Francois was very fond of her, but he was never very certain whether his liking for her was reciprocated. True, her people were very kind to him; they had given him more pleasure than he could ever hope to return. Often they had invited him to their house, which was much bigger than that of Francois' aunt. There they had looked through the illustrated books (there was a whole shelf full of them), they had gone down the mountain path on Adele's sleigh—it was a real one, with runners, and went, oh, so smoothly; they had taken him oftentimes when they went with the horses to the city, buried in the green valley where the river flowed. His aunt was poor and did not have a horse, so that he would never have gone to the city if it had not been for his friendship with Adele. But Francois had never done anything for her that she would ever remember. He had given her a carved picture-frame on her birthday which she had seemed to like, but it did not seem to draw her closer to him. She was Swiss and he was French. She was stolid, not easily moved to tears or smiles, he was filled with love for that country beyond the mountains; was easily affected—like the Frenchman he was—by the mere mention of tragedy, and his happiness flowed out of his heart whenever Adele invited him. She despised this weakness of his as well as his intense patriotism for the country which she thought he would surely never see again. She had little enough of imagination to realize what France was to him, even if he had told her of his mother's will. Often the sad truth dawned upon him that she was far removed from him, although they were great friends. How profound their friendship was no one could guess—that had yet to be proven.

One day, when he was nineteen, Francois was in the little village buying some groceries for his aunt. There was a commotion as if something important was happening. Shortly he found out there was a messenger from France who was going to read a proclamation within half an hour. Was it any wonder that Francois stayed to hear it? A messenger from France! Just to see him would delight Francois. In a half-agony of joy, the boy passed the long half hour. Precisely on time did the messenger ascend to the elevation in the centre of the square. All the inhabitants of the town had gathered to listen—they had no idea what he was about to say.

“I, the messenger of His Majesty Louis the Sixteenth, King of France and all French dominions beyond the sea, where the sun never sets, announce to you, citizens, that his Majesty is in grave need of special guards to protect him and his family. Therefore, O Citizens, if any of your sons are considered worthy of serving his Majesty, King Louis the Sixteenth of France, have the kindness to report to me this week in the village tavern where I shall rest. There I shall give you further details of your task.”

Thus it happened that, a few months later, Francois was a member of the Swiss Guard of his sacred Majesty which was lodged in the Tuileries Palace in Paris. The wishes of his mother were now fulfilled. He was serving the French monarch in a splendid red uniform, in which he was taught to shoot cannon. He received a few sous each day (more than he had ever received in one month in Switzerland) but rather bad meals. He was fairly contented, but for an occasional longing for Adele, the mountains and the sound of the cow bells. His special friend was a boy of his own age from another part of Switzerland, but Adele was neither mentioned nor forgotten. The farewell had been strange. Adele that week had had one of her cold moods, had spoken little and she had shown little emotion. But this had not daunted him and, knowing Adele, he knew that he could still think of her as a friend.

The times in France were very unsettled. No one in the Guard knew why, except the Commander, but he, of course, kept silent. They were not allowed to mix with people on the street, but were kept secluded in a barrack. There was a daily routine, only broken on Sundays, when they were given extra good meals. They knew that France was at war, but why and where they could but conjecture. Something was hidden, something that was to happen, something awful. Francois felt it, a mysterious sixth sense told him.

In June something did happen, but less awful than he had felt. One day they were told to be ready for an emergency. A great mass of crudely armed people had gathered before the Palace and presented a petition to the Assembly which was also housed in the Tuileries. They entered the palace and insulted their Majesties, but no order for action was given to the Guards, much to Francois' disgust. How terribly ill-mannered were these subjects of the king! He must do something to stop them; and the Queen, too—she was so very beautiful—he could not understand how they had dared to come so near her. Next time that should happen ... well, he would do something, he, Francois, would tell these people with ... with a couple of cannon balls.

The situation did not improve—France was being defeated abroad, Paris was very excited, the Guards had to practice harder. Francois' curiosity piqued him badly—why did they not tell the Guards what was happening? Why, they were his Majesty's own guards and they were not allowed to know!

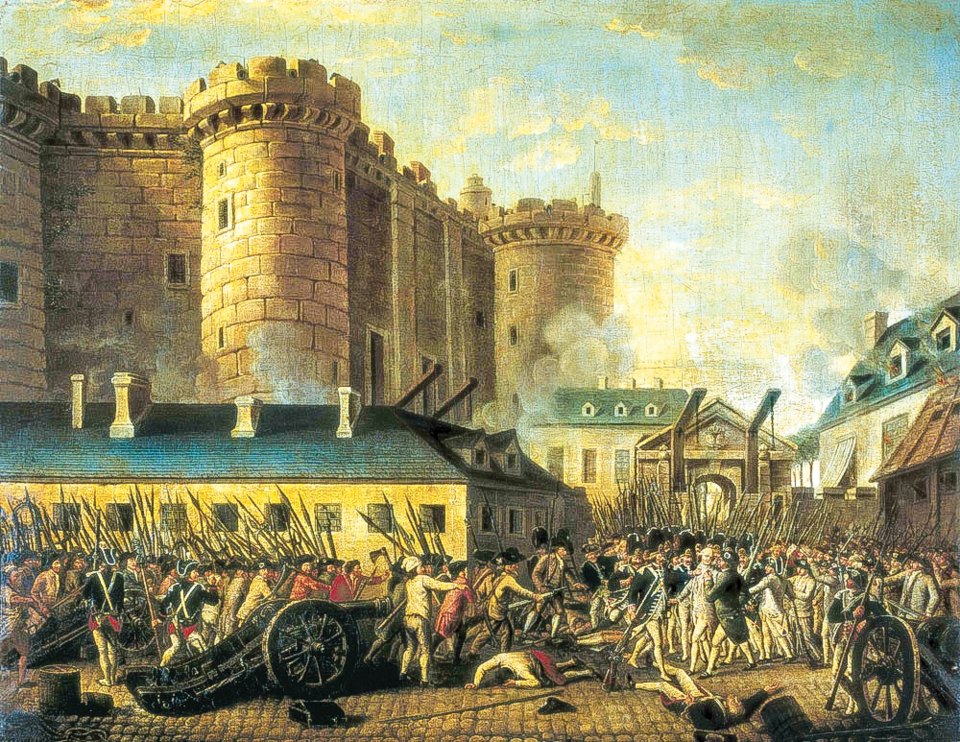

Late in the evening of August the 9th, 1792, the Guards were ordered to remain awake in arms, because some plot seemed to be brewing. At midnight a tocsin sounded. All Paris was in the streets. The Guards were stationed at vantage points in the Palace. The supreme hour had struck. No longer was there any doubt that things were going to happen and bad things. The large National Guard, the one that was always stationed around the Tuileries and beside the great gates, was strengthened by reserves; they stood, holding their weapons with grim faces gleaming in the torchlight, ready for action. The sky was clouded and it would have been pitch-dark but for the many lanterns in the hands of the warrior-citizens. The latter gathered thicker and thicker around the king's home, pushing the National Guards away with their pikes and shouting and screaming and singing revolutionary songs. They were becoming more furious every moment. Already the sound of clashing weapons was heard—the order of resistance and use of force was given to the National Guard—but it was too late. They disappeared, outnumbered, from the scene of their murdered commander.

By this time it was already the breakfast-hour. But the fates had ordained that few people in Paris should have breakfast that day. The Swiss Guards were in action, defending the old palace whence their Majesties had fled for refuge in the Assembly. The mob had become an army, poorly organized, but vast, omnipotent and determined to win a victory. His Majesty's last orders had been given several hours ago—to fight—and no other had arrived from the Assembly, so they fought, for his Majesty.

The slaughter was terrible. Francois had never imagined anything could be so cruel. He worked hard and courageously. Those ill-mannered people would be shown how to behave with sacred royalty. But towards the end of that day he realized that the Swiss Guard could not sustain mob violence as strong as that of enraged Paris. Many of his comrades had already fallen—he himself had several times come within an ace of death; his left hand was bleeding and his fine red uniform was dirty and torn. His ammunition was giving out. Fewer and fewer red coated Guards were left around him. Suddenly a bullet whizzed towards him, close to the ground. He felt a great pain in his thigh and fell to the foot of his cannon in a swoon.

A few hours later he was once more conscious of his position. There was not a Guard to be seen and the dull clashing and howling had moved to another side of the building, where the Assembly was being besieged. He realized that they had left him as dead and that now was his chance to escape with his life, or whatever there was left of it, for his leg hurt severely. Already it was dark; not a soul could be discerned. With infinite courage and faith he crept from under his cannon. He tore off his red coat, for people would recognize him too easily in it. Shivering a little, he tried to walk. He moved inch by inch; where was he going? He did not know, but his instinct led him westwards along the Seine and to the bridge over it. There he would hide! How strange that he had not thought of that before! There he could rest his weary limbs for the night and plan a course of action. He knew that he could neither remain in Paris nor return to Switzerland as a defeated soldier. Would Adele not then despise him more than ever?

Hesitatingly he crossed the old bridge over the softly gurgling river. It seemed as if he was in another world. Far away he heard the confused din of arms. He was all alone. A single star in the river caught his eye; the heavens were calm and serene. The soothing murmur of the waves beating the grey old arches calmed his distracted mind and a lone lantern at the end of the bridge cast long shadows on the pavement. A strange feeling swept over the lonely young man. He had not found the earthly paradise in his mother's country; his faith in the king of France, whom he had supposed all-powerful, was shaken to its foundations. In Switzerland he had not been completely happy—there were always those spells when he felt himself a forlorn and despised creature, when he feared that Adele did not return his liking for her and was cold and moody. Was he perhaps prideful? Was there some quality he possessed that could be blamed for his not finding bliss anywhere in this vast planet? Had his ambition to do something, something great, led him on a wrong path? Should he have remained in the mountainous country, where armies could not easily penetrate, and herded the village cattle in the summer?

He had reached the end of the bridge and was descending the bank to his prospective hiding-place. His thigh ached and he was all but breathless. With difficulty he crept under the stone structure. Some reeds crackled under his feet. He sat down with his arms clasping his knees, and prepared for a period of meditation with his eyes fixed on the slow-moving current. Suddenly he felt something move behind him. He stretched out a trembling hand to feel what it might be. It was something furry. A dog, he thought. Poor forlorn creature, just like Francois, had sought its shelter under the bridge. Now he would have a warm companion during the chilly night. But no, it was not a dog, it was bigger, colder... He kept on feeling. The creature moved—it was a human being. Was it another soldier or a citizen, who would kill him if he discovered that Francois was a Swiss Guard? He pulled the form from under the bridge. Suddenly he gazed on the fair face before him. The eyes opened and looked into his. Two hands were raised towards him from under the fur wrap that had hidden them. Soft music seemed to come from the stars that now appeared in splendid array, when he gasped: “Adele.”

But no, it was not Adele, but rather a slender girl whose resemblance to his beloved both shook him to his core and filled his heart with certainty. The two held each other silently, their mutual warmth warding off the cold. It was a sign from the heavens that was impossible to dismiss. Francois knew then beyond any doubt where—and with whom—his life belonged. The next day he would set out to return to the only home truly his own, and for the girl that he knew waited for him there. Francois and the waif drifted into sleep, the river flowing quietly below the bank, each dreaming of their own private, golden destinies. ◆

Editor’s note: “Faith,” slightly adapted here, was originally published in the 1937 edition of The Pelham Pynx, the yearbook/literary magazine of the Pelham Continuation School. (Its principal, Edward L. Crossley, would have a brand new high school named after him in 1963.) Author Eveline van Berkum was a Form 5 (Grade 11) student. There was little that a brief online search turned up to reveal details of Eveline’s life after she left PCS. In 1944, a Robbert van Berkum, possibly a younger brother, was awarded a PCS scholarship (and yes, “Robbert” is spelled correctly). Newspapers in Ottawa and Vancouver reported an engagement in 1952—but the details are behind a paywall. Eveline would be close to 100 now. If you know anything about Eveline, please let us know: [email protected]