BY PETER NICE as told to Larry Coté

My name is Peter Nice and I wish to recollect for you one of the chapters of my life. I was one of the English child evacuees during the Second World War. We evacuees lived in major urban cities and coastal towns in the UK that were thought to be potential targets for German bombing raids and possible invasion.

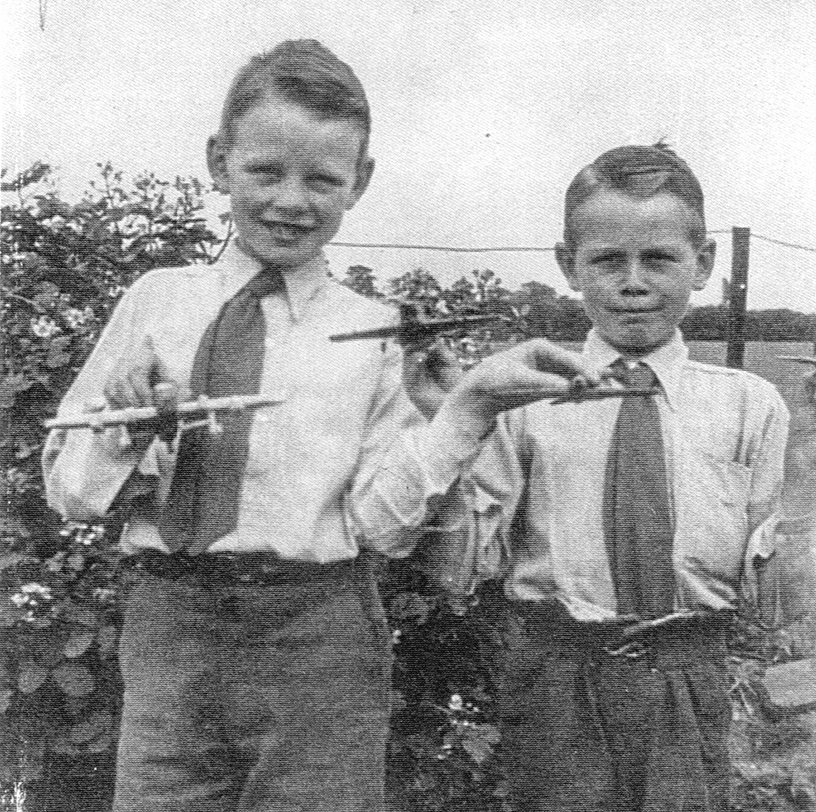

I was born 87 years ago, to Daisy and Edwin Nice, in Clacton-on-Sea, a seaside town about 72 miles northeast of London. I have a brother, Edwin, who is one year younger than me. My father was an engineer with the L.NER, a major railway company and, as an essential service worker, he was not conscripted into the armed services. The nature of his work required him to be away from home very often.

Near the beginning of the war, in 1939, the government announced a program that was intended to save children, pregnant women and a few other vulnerable people from the German bombing attacks. The program was codenamed, “The Pied Piper.”

Due to the dire nature of this emergency war measure, the scheme was hastily implemented. More than a million children were relocated from many urban and coastal towns to more rural locations throughout the UK, and even to some far-flung locations such as Canada, Sweden, and Norway.

Before the evacuation, my brother and I attended Holland Road School, where we were provided with gas masks to be carried with us at all times in a little cardboard box.

Basically, this is how The Pied Piper program was implemented: my mother was advised, with very short notice, to pack one small suitcase and a backpack with essential personal items for both Edwin and me. My mum was told that, for our own safety, we were being sent to an undisclosed rural community at some distance from our home. We children were not told the detail of these plans. Rather, we were intentionally misled and told we were going on a vacation trip or a play camp somewhere. Children of more wealthy parents were alternatively sent to family cottages located in the countryside or boarding schools at some distant place.

On evacuation day, June 2, 1940, when Edwin and I arrived at Clacton train station, we were issued name tags to be worn at all times and given a pre-addressed postcard. This card was to be mailed back to our parents once we arrived at our, as yet, unknown destination.

And so it was, my brother and I were taken by train to London Liverpool Street Station, thence from Paddington Station by train to Kidderminster, and then by bus to the village of Far Forest—population about 500. Upon arrival at the Village Hall we were each issued a blanket and told to rest on the cold, damp floor. We were fed rather sparsely and any sort of personal hygiene was at a premium. My brother and I stuck close to each other throughout this abnormal ordeal and feared separation as our mother had forewarned. She admonished us to watch out for one and other every minute of every hour, and that we did.

The next morning we were lined up against a wall and members of the community and nearby villages were asked to come by the Hall and choose a child whom they would billet until the indeterminable end of the war. Each of us children stood there with the earnest hope we would soon hear the portentious words, “We’ll take that one.”

Fortunately for my brother and me, we were both chosen to remain together by a wonderful couple named Jim and Lucy Bates. They lived in a bungalow located on “Plough Lane,” approximately a mile off the main road. This address was aptly named as, in fact, it was located in the middle of a forest glade with no electricity nor indoor plumbing. Edwin and I had to learn to live by lighting up the night with homemade wax candles and smoky kerosene lamps. This wonderfully generous couple had two very young children of their own, a little boy and girl. And yet they responded to this special call for help. For some reason not evident to us, our foster father had some type of disability, causing him to be ineligible for military service. But whatever the disorder it certainly did not preclude him from being an excellent provider for his family, including Edwin and me.

Imagine, if you will, this young couple taking into their bungalow two very young boys they had never met or seen before and take full responsibility for their needs and cares for an indefinite period of time, and with only a pittance of a support payment from the government. For Edwin and me this began a period in our lives that would be etched in our memories forever. We lived with the Bates for just about two-and-a-half years. During that time, we had brief visits from our mother on maybe two or three occasions. Given the nature of the times, missing our mother and she missing her two boys did not count for much in the context of the war.

As guests, we had duties to perform around the homestead—chopping wood, digging holes for sewage disposal, pumping water from the well to fill the cistern in the ceiling of the house, picking fruit and other chores suitable for our ages. When the cherries were ripe on the trees we students were given a week off school to help harvest the crop. There was a very large orchard with large, prolific trees right on the edge of town, which I believe was owned and cared for by the Trolleys, our foster mother’s parents.

One chore incident remains in my mind. I was chopping kindling for the very hungry cooking stove in the house. Somehow or other, I missed the log and struck my ankle with the axe. While my foster mother rendered first aid my foster father ran to borrow a truck to take me to the hospital in Kidderminster, some miles from home. The doctors there tended to my wound, instructed my foster father on the home care needed, and we left for home back in Far Forest. The pain of healing was made worse by the embarrassment of mistaking my ankle for a log. That scar is a reminder of those days even now.

During the school year we attended Leas Memorial School, which accommodated about 360 students. Mr. Bates, our foster father, using a borrowed truck would sometimes drive us to school in bad weather. Mrs. Bates would pack us a sandwich for our school lunch. It was a large slice of bread with drippings and Marmite. For those unfamiliar with that iconic English food spread, it was a yeasty by-product of the beer making process. We did not like these lunches and often threw them away without telling our mum. We had to walk back to the homestead after school and it was a lengthy trek. Due to the remoteness of the location we never saw any military personnel or equipment during our stay.

I must tell you that while our adoptive parents were a wonderful match for Edwin and me, not all billeting arrangements were amicable. The match of child to foster parent was a lottery. Some were unhappy alliances and, frankly speaking, a few were traumatically atrocious. When the end of the war seemed imminent, the program was to be ended and the evacuated children were to be returned to their former homes. More than a million children were reunited with their birth parents. There was a bit of a kerfuffle for us as our parents had moved twice and were now living in Colchester. However, we were successfully reunited in the spring of 1943. Sadly, many children were never reunited with their birth families. There was much confusion due to the large numbers involved. In some cases, children arrived back in their home town only to find their families were casualties of the war, and at this tender age discovered they were orphans, with no place to settle. That is but one of the tragedies of war.

Thankfully for Edwin and me, our good fortune continued and we were reunited with our parents. Our former home town of Clacton-on-Sea mostly escaped war damage but for an accidental dropping of a mine by a wayward German aircraft that did some damage to the Grand Hotel. It is believed that this plane subsequently crashed into the North Sea. Another aircraft, running short on fuel, attempted a landing and mistook the railway track as a landing strip. It crashed and shattered the windows of nearby houses, but remarkably, except for the German pilot and two other victims, the damage was minimal.

After the war, we continued to have a close kinship with our foster parents back in Far Forest. My brother and I, and our family, owe them an unrepayable debt of gratitude. We communicated with them frequently over the years following the war and visited whenever the opportunity presented itself.

Although my brother and I, together with many others, suffered a certain amount of deprivation during the war, such as not seeing our parents for long periods of time, with no toys or radios, we survived. Today, I sometimes wonder how those protesting the wearing of masks would cope with the multitude of restrictions imposed by a government during a war.

For us, the Pied Piper program was a noteworthy success— a literal life-saver. There are many horror stories to be told about the tragedies of war. Hopefully, this episodic event represents an opposite outcome. ◆