Special to the Voice

I recently posted a picture on Facebook of the Town of Pelham raising the Pride flag in recognition of Pride month. I was very happy to see the Town made the decision to raise the Pride flag and was also very impressed with the nice comments and the amount of likes I received on my post. I was also informed of how much opposition there was in recent years for raising the Pride flag not only from the community, but also from Town Council.

I was asked to write about my experience growing up gay in the Town of Pelham. I’ve never told anyone the full story and I will attempt to write it without too much drama. I hope my story won’t offend any of my family or friends, but I think it’s an important story to tell as I hope it will inform people of why pride symbols are so important.

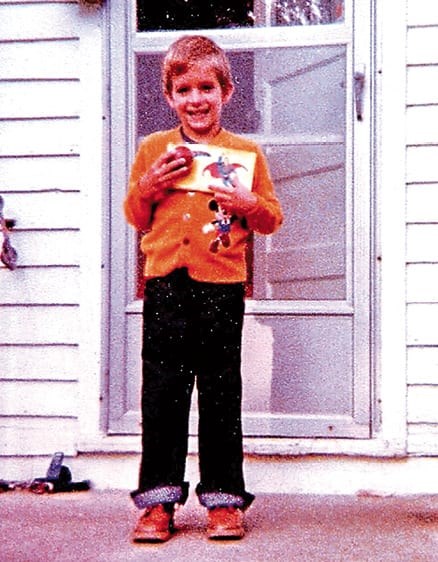

The first time I was teased about being gay was in Grade 1. A few Grade 5 boys made a joke about me being gay. I didn’t understand the joke nor did I know what being gay meant. I went home and asked my brother what it meant and I don’t really remember what his response was. What I did understand that being gay was a very bad thing.

As school continued, the bullying got worse but was overlooked by most teachers. I did have a few friends and they made public school bearable for me. What started to develop was my hatred for gay people. I had no idea what my sexuality was, so I couldn’t understand why people always teased me about being gay. What I did understand was gay people were bad and if there were no gay people, I wouldn’t be teased and bullied. I hated the fact that gay people existed and I wanted them all to die so people wouldn’t think I was gay.

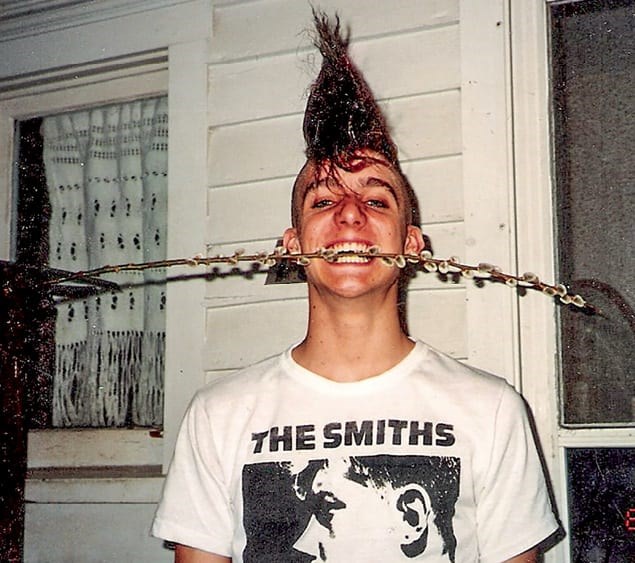

As I got older, I tried everything I could think of to try to prove to people that I wasn’t gay. Some old-time Fonthill people may remember I had a mohawk haircut for a number of years. My rationale was being “punk rock” was the opposite of being gay. How could anyone believe that I was gay if I was punk rock? Unfortunately, this didn’t help and only made the bullying worse. In Grade 9, a group of boys decided they would put Neet hair remover in my hair. I was a pretty fast runner and eventually called my mom to pick me up early from school. My hair remained but I realized that the next four years of school would be hell.

Not every day was this bad in high school. I had a number of friends that I hung out with. My sexuality was never a question for them. A normal day at school would consist of being pushed into lockers a few times a day, being called a faggot more than a few times a day, and kids would typically throw rotting fruit at me when I got off the bus at the end of the day. Few teachers ever intervened, even if they saw what was happening. Sometimes my music teacher would let me hide in the music room for a period or two if the bullying was too bad that day.

It was during my high school days that I started to really understand what being gay meant and I also started to admit to myself that I might be gay. That was the period that my hatred of gay people started to shift from hating an abstract idea, “gay people" (I didn’t know any gay people personally at that time), to starting to hate myself because I might be a dirty faggot. People would often tell me, “If you just act normal, you wouldn’t have so many problems.”

The issue was, when I was acting normal that’s when the bullying started. I tried acting straight—it didn’t work. I tried so hard to change myself into someone that wouldn’t be hated by society.

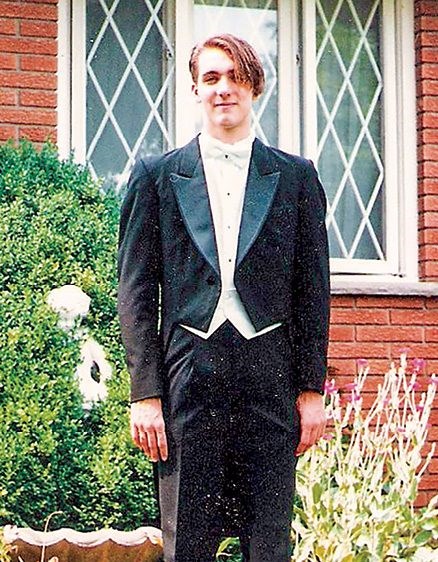

A good friend of mine was murdered in 1988, when I was 17. My life completely changed. I changed my hair and my clothes, I didn’t really care how I looked. I was in a daze for most of the next year. I don’t really remember school that year as I didn’t attend often. Instead I went to Toronto to attend the preliminary hearing of the man that murdered my friend. When I was at school, the bullying didn’t seem as bad. I’m not sure if the kids new how fragile I was that year, or if I just don’t remember.

That didn’t mean the bullying outside of school ended. I was often beat up when walking in town, usually not too badly. I was typically able to hide it from my family. There were only a few times I was bloodied. The bullying also included a number of incidents of vandalizing my car, including slashing all four tires, breaking all the lights, and smashing the windows.

The bullying and harassment also followed me to work. I was a lifeguard and swimming instructor at the Welland YMCA and Brock University. Along with the typical name calling and pushing, parents complained to my supervisor about me teaching their children. They were concerned that I might be a pedophile and that I would molest their children.

I also was the pool manager at the Pelham pool. Those were a couple of great summers. The majority of the kids and parents were wonderful to me. I think by then, I had figured out how to “act more straight.” There were still a number of incidents of vandalism of the pool because of my perceived sexuality. It was often spray painted on the walls of the pool building.

I left for university in 1990 but decided not to go back for my second year. Instead I started working for the federal government. Within the first year of working, my manager called me into her office and told me that “You are like the sun, but you need to turn into the moon.” She said that if I wanted a career with the government, I would need to be “normal.” In the ‘90s, it wasn’t good to be gay in the federal public service. Although I tried to hide it, a lot of people assumed I was gay. I was passed over for advancement a number of times because I was told that I wouldn’t be taken seriously because I was too effeminate. Fortunately, I had some allies at work and was able to gradually advance with their help.

In 1991, I started to accept the fact that I was gay and was starting to become comfortable with my sexuality. I came out to a few friends, started going to gay bars and met people “like me.” I was still afraid to come out to most of my friends and family. Although I knew my family would support me, I was afraid they would be disappointed in me. At that time, it meant no grandchildren would be coming, and the fear of HIV/AIDS was very real and in the forefront of the gay community.

We aren’t a special interest group, we are members of your community

I also had to worry about how the community would react to my sexuality if I came out. My family was in the restaurant business — had been since 1952 — and the reality was, if people knew I was gay, they would be some that would no longer patronize the restaurant.

Eventually I told my mom and my brothers to mixed reactions. In the end, they accepted me and always supported me. It was difficult for them in the early years and we didn’t talk about it much.

The next 20 years have been a dance of being out to close friends and family and being careful of what I say to colleagues and acquaintances to try and not to be obviously gay. I didn’t always do a good job of that.

I recently read something that really struck home with me. It reads “queer people don’t grow up as ourselves, we grow up playing a version of ourselves that sacrifices authenticity to minimize humiliation and prejudice. The massive task of our adult lives is to unpick which parts of ourselves are truly us and which parts we’ve created to protect us.”

I am happy to say today that I am a proud gay man. I am happy and impressed that most of society in Canada has evolved to accept the LGBTQ+ community, however we still have a long way to go.

This was brought clearly into focus for me when I realized I needed to talk to my mom before I wrote this.

I will not personally experience any negative reaction from writing this. I no longer live in the Town of Pelham and only visit a few times a year. If someone has something derogatory to say to me about my sexuality, I won’t care. At 50, and having been harassed and bullied for most of my life, I have developed a very thick skin and have heard it all.

My mom, on the other hand, still lives in Pelham and is very active in the community. We both understand she will receive the brunt of any negative reactions people have to this story. We both agree that true friends won’t care—that’s been my experience with every friend and family member I have come out to. There will be acquaintances of my Mom’s that will have an issue with my sexuality and may stop speaking to her or will treat her differently. It shouldn’t be that way.

I often hear people talk about recognizing Pride month, or Pride day as showing favouritism to a special interest group. We aren’t a special interest group, we are members of your community. By flying the Pride flag or installing some rainbow benches, you as a Town and a community are saying everyone is welcome. It doesn’t matter is you're gay or straight, black or white, male or female, or any other colour of the rainbow, you are welcome here.

Depression and suicidal ideation were my constant companions until I became comfortable and proud of who I am. If flying the Pride flag, or having a rainbow bench can let one young person know that they are accepted by their community and spare them some of the trauma I experienced growing up, it is well worth it. I cannot understand why some people are opposed to this. It doesn’t hurt anyone in any way. If the Pride flag offends you, don’t look at it. If a rainbow bench offends you, don’t sit on it. If a gay person asks you to marry them, say no (unless of course, you think they're cute).

I hope this story will help people understand why symbols of Pride are so meaningful. When much of the world is telling you it’s not okay to be who are—in TV, movies, advertising, etc.—it is imperative to have a symbol of hope to tell you things will be okay and your life has value. ◆

Contribute your story to our Pride series on growing up LGBTQ+. Email [email protected]