Each week’s schedule is pretty much the same in our house—up early on Mondays and Tuesdays, sleep in a bit on Wednesdays. So it was a little unusual to find myself suddenly awake last Wednesday at 7 AM, staring at the ceiling, wondering what was up.

My abdomen quickly let me know. There was a hellacious pocket of gas in there that wanted out. I slipped in to the bathroom to search for a packet of Alka-Seltzer tabs.

A half-hour later the sensation was worse. I took two Ibuprofen for the pain, which had turned stabby. My abdomen was also bloated, especially around my belly button.

Things went rapidly south from here. A generalized feeling of unwellness descended. I was feverish and chilled at the same time. I started to dry heave over the kitchen sink.

At 8 AM I woke up my wife, Yasmin, and said that I was calling an ambulance. At this point my lower back had joined the pain parade, with intense aching around both kidneys. Dammit—could this be kidney stones?

I’d heard many a tale from sufferers about how kidney stones gave them the worst pain of their lives—most recently, as luck had it, from a campaign official working with one of the Niagara West parliamentary candidates in last month’s federal election. “Never been in such agonizing pain in my life. Still there but duller. No sleep since Friday night,” they emailed the following Monday.

So that’s what I told the 911 operator through gritted teeth: “I think it’s kidney stones.” Ever experience this before? she asked. “No.”

From here on the day’s timeline gets a little fuzzy, since it was suddenly evident that one part of my body was trying to kill the rest of me and I really had to concentrate on making sure this didn’t happen.

At about 8:30 the ambulance arrived. Two young paramedics, one male, one female. They were professionally calm. I suggested my right arm for the IV, which is usually easier for routine blood draws. After two failed and painful attempts on my left hand and left forearm, they gave my right hand an equally futile try. They finally decided to go with what they called a big dose of non-narcotic painkiller injected into my left shoulder. It may as well have been water. By the time I was loaded into the ambulance, my entire abdomen and lower back were in boiling agony, and getting worse.

It was as if a medieval torturer had heated a sword and two iron rods over a roaring fire. The sword was twisting in my belly, right at the navel. The iron rods were embedded deep on either side of my lower back. I could not lie still. So this is literally what writhing in agony is like, I thought, as I writhed in agony down South Pelham, to Webber, to Welland Hospital.

After what seemed like an eternity, an E.R. nurse successfully got an IV going in my right arm and started a morphine drip. This didn’t touch the pain either. I started vomiting brown gastric juices, which kept coming, and coming.

I was wheeled over for a CT scan, given an injection of contrast dye after I signed a consent form, and told to stay as still as I could even if I felt a burning sensation from the dye (yes, but the least of my problems).

Hours passed. Yasmin arrived at some point in the early afternoon. I felt bad for not having texted her earlier, but it was impossible to think of doing anything with my hands other than gripping the sides of the gurney and contorting my torso to see if one position would provide some relief over another. I dropped F-bombs. I groaned, loudly. And still it got worse. I became nothing but a manifestation of pure pain.

It’s one thing to watch a Hollywood war movie in which a wounded soldier begs a buddy to put him out of his misery. The real sensation is not entertaining in the least. I will never forget how this agony made death thinkable, if just at the periphery. I was in a hospital, I was going to be treated, yet I was still barely coherent. Don't let what may come across as a breezy tone here fool you—this was by far the worst experience of my life.

Finally a Dilaudid opioid drip was started. This brought the pain down from a 10 to a 4, enough that I got most of my wits back.

A surgeon arrived and said it wasn’t kidney stones after all.

The CT scan showed a twist in my intestine—not something that you want to let go for long, for fear that the rot spreads into an irreversibly fatal outcome.

In the end, they took out about a foot—25 cm— of small intestine. The next day the surgeon told us that when he opened me up it looked very bad, yet there was no clear obstruction, no evident reason that the intestine should have twisted or folded upon itself.

It happens, he said. “We don’t know why.” It can happen to anyone, anytime.

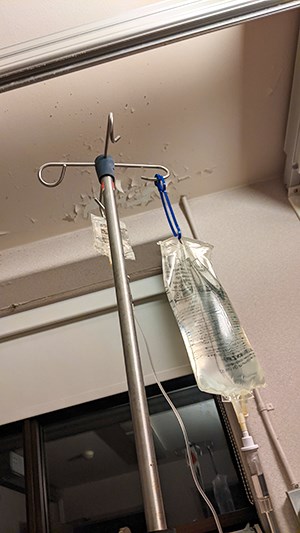

Now to the reason that I decided to tell you all this. Imagine that you had experienced this yourself, and then post-surgery you woke up on a hospital ward that was grossly understaffed. What does this mean? It means that while the two nurses on duty are taking care of some of their patients, other patients in other rooms are literally screaming out in pain, pleading for help. It means that when you ring the call button for help or medication, the response may be 20 minutes away. It means that the automated alarms that sound on IV drip machines, when they run out of liquid, echo up and down the hall because there aren’t enough staff to get to them to turn them off and replace the bags in a timely manner.

Take a moment to consider what this is like at night, in the half-dark. These call bells and IV alerts sound like a mix of elevator dings, and smoke alarms at half volume. There's nothing gentle about them. They keep repeating, steadily, until they are turned off. But the longer an IV alarm goes without being answered, the louder it gets.

Now consider that it’s your IV alarm, and it’s 3 AM, and getting steadily louder a metre from your head. Wait five, ten, 15 minutes. You hear similar sounds and call bells out in the hall, endlessly repeating. Patients yelling, some kicking at their beds. How long before this bedlam becomes its own goddamned trauma?

I want to make something very clear: every staff member I and my wife encountered during my stay seemed to be doing the best job they could under the circumstances. They were polite and professional. What is appalling are the circumstances under which they are expected to work. This pre-dates the pandemic, but Covid has made their work lives exponentially worse. Forget the peeling paint and curling wallpaper. It's the under-staffing that can turn it into a level of Dante's Hell and usually does. One nurse told me she can’t endure working even part-time any longer and will shift to casual. Another said she’s getting an advanced certificate that will allow her to work anywhere in the world—that is, away from Canada, and particularly Ontario. This burn-out threatens to burn down the entire system.

You may be the deepest blue, budget-slashing, small-government conservative in the history of Niagara voters, but I guarantee that if you’re forced to spend four nights—which was a fast discharge for the surgery I had—enduring what I did in recovery, you would willingly hand over a significantly higher chunk in taxes to make sure it never happened again, to you, or to a loved one.

Ironically, as I tried to cobble this week’s paper together on an old laptop in my hospital bed, I noticed a press release in my inbox from MPP Sam Oosterhoff, boasting, “Ontario Investing in Hospitals in Niagara.” Some $53 million is evidently coming to Niagara Health— which qualifies because it has hospitals whose “current liabilities exceed their current assets.” In other words, they don’t even have enough cash to carry on at the current level of service. I'm no expert, but I'm pretty confident that $53 million is a drop in the bucket.

This isn’t just a Ford or conservative government failing. Somehow public health in Ontario has always seemed to take a backseat to sexier issues. Yet a government’s first priority is by definition the health and welfare of its citizens.

I will forever be thankful that my surgery occurred as quickly as it did, in the competent hands of health professionals who, despite the maltreatment shown to them, continue to show up every day to chase IV alarms, to run CT scanners, to cut out failing body parts. At least for now.

A tube stuck down my throat has left my voice raspy at best, and for the next six weeks I’ll be lifting nothing heavier than a 2012 MacBook Pro, so my editorial barking will be on the muted side. Here’s to your good health, and to a belated Happy Thanksgiving. ◆

Dave Burket is publisher of the the Voice.