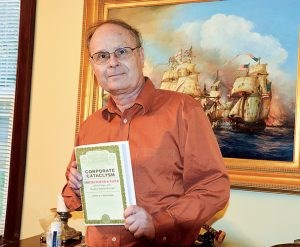

Retired professor Barry Boothman honoured by Ontario Historical Society

A scholar turned award-winning writer is in our midst.

Barry E.C. Boothman, a Fonthill resident for almost a decade, has been honoured by the Ontario Historical Society with the 2020-21 Fred Landon Award for his book Corporate Cataclysm: Abitibi Power & Paper and the Collapse of the Newsprint Industry, 1912–1946, published by University of Toronto Press. The award is given annually for the best book on local or regional history in Ontario.

Boothman retired in 2012 as Associate Dean of the Faculty of Management at the University of New Brunswick, where he spent most of his professional career.

Boothman’s tome was lauded as a “rigorous and insightful case-study” of Abitibi, the mammoth pulp and paper corporation which was headquartered in Toronto during the first half of the 20th century. Boothman documented the company’s spectacular rise and fall, with an analysis that connected the strategic development of Northern Ontario's newsprint industry with the political forces in play at the time.

The Ontario Historical Society customarily has a formal dinner and awards ceremony, but given these Covid times, Boothman gave an acceptance speech that was released as a video.

The Voice sat down with Boothman at his Pelham Street home recently to discuss his book, politics, and highlights from his career in academia.

Corporate Cataclysm is spread over 15 chapters, and at 645 pages is a comprehensive and deeply researched read, considered the definitive account of the Abitibi Power and Paper Company’s first insolvency. (Abitibi, in a later incarnation, underwent a second insolvency in 2009, when it was the world’s largest publicly traded pulp and paper manufacturer.)

Despite its length and complexity, Boothman asserts that “this is a book anybody could pick up. There are a couple places where it could be heavy going, but I have a fairly fluid writing style, and I remember who my audience is.”

Boothman feels that there was no primary factor that led to Abitibi’s financial problems. Rather, it was a result of myriad circumstances and events, which the book dissects and discusses.

“Writing Corporate Cataclysm was fun for me, because it’s a virtual who's-who of Ontario business, law, and politics at the time,” said Boothman. “A long series of scandals unfolded, and Abitibi was headline news in Ontario newspapers from 1927 until its receivership in 1946. Abitibi was the biggest hydro project after the Sir Adam Beck Hydroelectric Complex in Queenston. It was built as a private enterprise, and went bankrupt. The Ontario government had to take it over. They couldn't allow this thing to deteriorate, and they also couldn't take the chance of a private sector monopoly being established. But nobody knew at the time that Ontario Premier George Henry had $25,000 in Abitibi bonds, and didn't disclose it. The opposition Liberals were convinced that this was thoroughly corrupt, and they crucified him in the 1934 election.”

In 1939, asserts Boothman, after Abitibi had declared bankruptcy, a group took over the bondholder committee and essentially decided they were going to steal the company and put it up for public auction. This turned into a constitutional crisis, and the government had to intervene.

“The government couldn't take the risk, especially in wartime, since they had American and British investors who stood to lose their money. The government first tried a Royal Commission, and then tried to impose a moratorium. My book uncovers a lot of fuzzy financials, creative accounting, dubious ethics, on all sorts of partnerships. But it's all presented objectively, according to where the evidence took me.”

Boothman attended Sir Winston Churchill Secondary School in St. Catharines, and went on to study history at Brock, before subsequently earning an MBA and PhD at York.

“My father made me work in a steel factory during the summer months, and I pretty quickly got it through my head that if I didn't improve my grades, this is how I might be spending the rest of my life,” he said with a laugh.

He evolved into a business historian, and taught at a number of universities, before landing at the University of New Brunswick.

“I planned to be [at UNB] for three years, and ended up staying 26,” he said. “UNB gave me the best deal, in terms of teaching business strategy, international business, and corporate governance, and being able to do interdisciplinary research. The university had partnerships with institutions in Trinidad, Ukraine, and Singapore, and I visited all three at different points.”

The late Brock philosophy professor John Mayer was a teacher who had an impact on Boothman.

“Professor Mayer taught me one of the most useful courses, on ‘symbolic logic,’ said Boothman. “I've used his concepts as a consultant, and in developing my expertise in corporate failure and bankruptcy. I often told my students that we learn a lot more by studying failure than by studying success. Failure is a lot more fun to study as well. You don't get into the hype of executives trying to convince you of how wonderful they are.”

Much of Boothman’s research involved poring over lengthy corporate financial documents, engineering statements, and the like.

If you've been trained in symbolic logic, you learn to just step past all that and find the few paragraphs that actually matter

“People would ask me how I was able to get through all that stuff, and I would respond that, first of all, you have to recognize that 90 percent of it is meaningless,” said Boothman. “It's codicils and legalese and copious financial data. If you've been trained in symbolic logic, you learn to just step past all that and find the few paragraphs that actually matter.”

He cited the case of former New Brunswick Premier Frank McKenna, a Liberal, who back in the early 1990s pushed to replace a section of the Trans-Canada Highway in his province. The feds would not contribute to the billion-dollar project, so McKenna sought a partnership with a contractor, and planned to pay for the roadwork with highway tolls, which were despised by the populace.

“The CBC came to me for an analysis of the contracts, because I had done work on public-private partnerships,” said Boothman. “The documents I reviewed ran to about 3000 pages in length. The reporters couldn’t believe how quickly I finished my assessment. I told them that the bulk of the document was engineering specs, with about 15 pages of financial information, of which one single page was crucial. It explained how they were planning to finance eight percent of this deal — the biggest in New Brunswick history — while 92 percent of the cost coverage was ‘to be announced,’ meaning that they hadn't figured it out yet.”

Boothman explained that highway tolls in Ontario make sense, because high traffic volume occurs 12 months of the year.

“But in New Brunswick, you've only got significant highway traffic four months of the year,” he said. “You do have transport trucks going through, but not at the volume to make it economical. From a strictly business, economic perspective, with no ideology involved, this made no sense at all.”

McKenna’s Liberal government in New Brunswick was replaced by the Conservatives, who scrapped the whole toll arrangement. The debt, of course, was loaded onto the provincial taxpayers, who continued to pay off the highway through a “shadow tax” of about $20 million a year.

On another occasion, Boothman was brought in as a consultant when Canadian department store chain Eaton’s was foundering.

“I gave them my advice, and they didn’t apply any of it. Four years later, they went bankrupt, and lost everything. The worst part was that when the company dissolved, the workers’ health trust was treated as part of the company assets, which were seized by the creditors. I’ve done countless interviews with the CBC and CTV, saying that if you're a worker, especially if you're in union, make certain that your healthcare benefits are set in a proper, legally protected trust so that if anything happens to the company, your benefits will be intact.”

Boothman said that he criticized both Liberal and Conservative governments for not changing the bankruptcy law decades ago, to make certain that worker pensions and benefits are the first thing protected.

“Bondholders will eventually recover their money one way or the other. They'll sell off the company assets. If you understand corporate finance, you know how things actually play out. The board is rigged in their favor. But politicians need to remember that companies don't vote, people vote. You've got to pay attention to both interests.”

Boothman doesn’t believe in corporate welfare and corporate subsidies, not because of political ideology, but because of raw economics.

“As an academic, I know subsidies are not what drives the decision in any company. The reality is most companies are making the decision based on market share, product quality, and market attributes. They've done their research. They know whether they're going to go ahead or not. Subsidies are simply icing on the cake.”

Boothman is recovering from a rare type of lymphoma, and has a compromised immune system given the chemotherapy that he endured.

“My energy isn’t back to normal yet. I don't cut the lawn anymore. That's all been contracted out to Dekorte.”

But he is busy working on a new book, which he is hoping to finish next year.

“My working title is Continental Drift, a study of the emergence of Canadian-American business relations from approximately 1783 to 1860. If the gods permit, there will be a sequel, Continental Union, which goes from 1860 to 1930,” he said.

“The standard image most people have of pre-Confederation Canadians is that they were crude, homespun ‘pioneers.’ Which wasn’t true at all true,” said Boothman. “It was a market-oriented society already, trading in a remarkably diverse range of products. People keep over-simplifying past societies.”

Turning to the current political scene, Boothman said that he’s not prepared to go out on a limb and predict how the provincial election is going to go next year.

“My suspicion is that Doug Ford and the Tories will get back in, but with a significantly reduced majority. And I won't be surprised if the Liberals are returned as the leading opposition party again, although Kathleen Wynne nearly drove the province into the ground. I like Andrea Horwath of the NDP personally, but she doesn't have people capable of handling cabinet level jobs. You can't run a government on one person.”

Who does Boothman consider to be the heir-apparent to head the Liberal Party when Justin Trudeau ultimately steps down?

Perhaps Canadian economist and banker Mark Carney?

“I think the person who wants it — whether she can get it is another matter — is [deputy prime minister] Chrystia Freeland,” he said. “But the harsh reality is I don't think she's got the strength to hold the position for very long. The Americans walked all over her during the renegotiation of NAFTA, even though the Canadian media didn't present it that way. My contacts in the British government don’t think too much of her, but they think even less of Trudeau.”