Thoughts of past Christmases spring from a forgotten relic

As she drives her car west past Haist Street along Highway 20, she has to strain to spot something she has noticed many times before — a remnant from the past, a thing that seems to no longer fit . . . an endearing time capsule.

Christmas is days away.

She steers the vehicle past the familiar enclave of commercial businesses that have sprung up over the years on both sides of the roadway where fruit orchards and farms once thrived. A retirement residence fills one corner of a block.

Gone are the majestic chestnut trees and maples that stood along the south side of the highway, gone now for so many years. They once provided summer shade for long-forgotten orchard workers — cherry pickers like herself, then a teenager — taking a midday break and a refreshing sip of cold water obtained from a nearby farm well.

Summer then, winter now. The snow is falling gently on this particular December day, melting almost instantly as the thick flakes collide against the windshield, quickly swept away by the incessant movement of wiper blades.

It’s not as cold today as she remembers the weather being back then, this close to Christmas — when the entire family gathered at the farm.

Ah, the old farm. A memory stirs. The farm was situated on the south side of the highway, where the two Lookout Village condominium residences now stand. She remembers there were far fewer cars and trucks on 20 Highway back then. So few, in fact, that Terry, her grandparents’ old farm dog, decided one day to plop down in the centre of the roadway, indifferent to the occasional cars passing by, their drivers slowing down, driving around to avoid him.

That wouldn’t happen today, she tells herself. Not on this fast-paced artery.

Not anymore.

Now a woman of 80, Brenda Sauer was a young girl then, living in Welland, being dropped off by her working mom and dad several days a week to visit her grandparents on the farm, and — more important to her — to spend time simply playing with her same-age cousin Virginia (everyone called her Ginny), who was then living with her grandparents

“How old was I then?” she ponders. “Five? Six?”

Pause.

“How I miss those days.”

Now, as the site of where the farm stood approaches, the thought of those long-ago Christmases evokes a shiver. They were the festive holidays that she remembers most fondly. Christmas Days spent at the farm. It’s a nostalgia that seems to be fed this time every year.

Craning her head toward the driver-side window, Brenda suddenly spots it — a solitary water pump, its wooden handle pointing to the sky like a gnarled old finger. As a child, she used it to pump water from an underground cistern. Now the pump sits frozen in time. The sight becomes a locked-in image in her mind as the car continues down the highway.

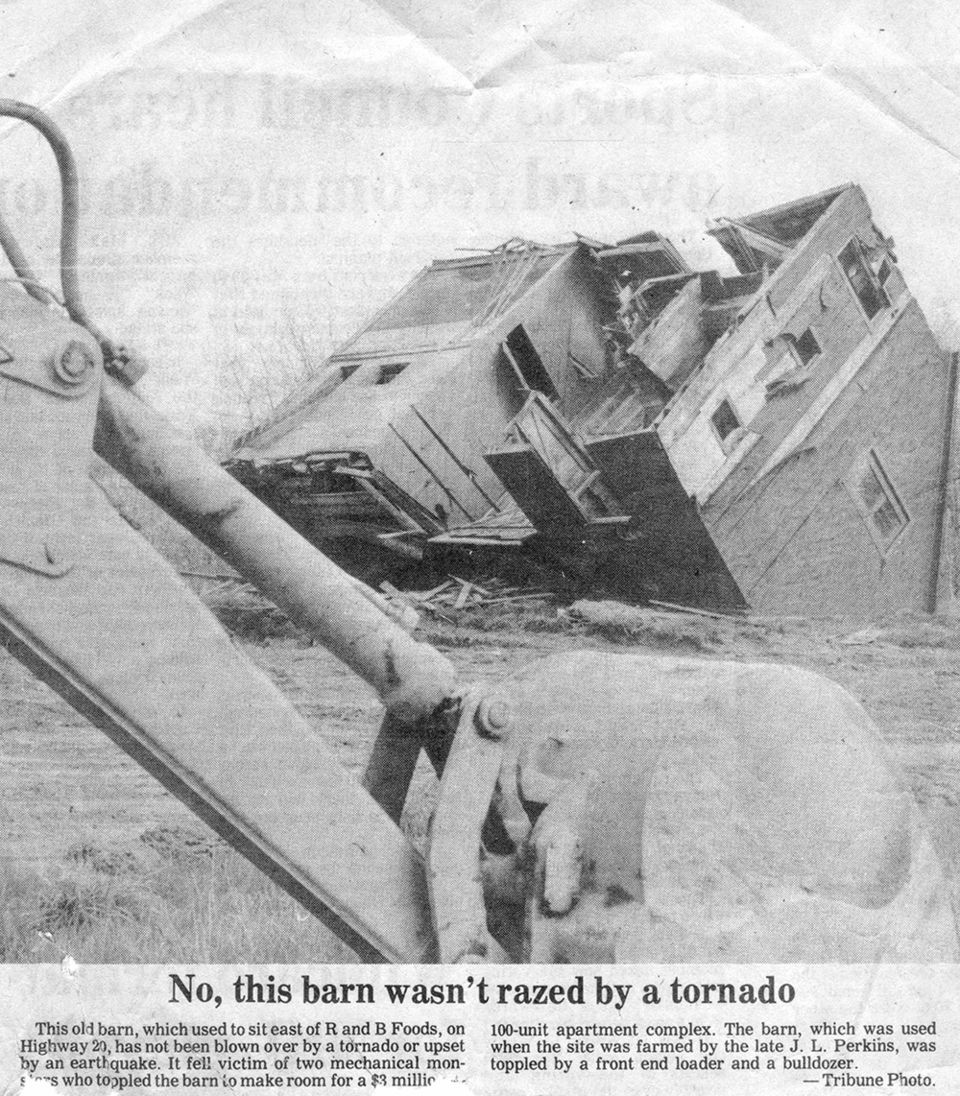

“Why is that thing still there?” she wonders. The farmhouse, barns, the entire orchard — all gone. Gone for years, condo apartments now in their place. The water pump and several old pine trees are the only evidence of the farm that remain.

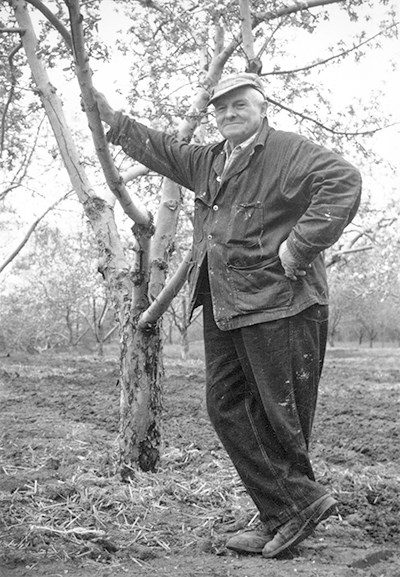

It has been scores of years since the pump was last used. But Brenda remembers vividly the sight of her grandfather, John Leroy Perkins, using it daily to quench the thirst of his two farm horses.

“He watered the horses in the morning and the evening, and if they had been worked hard he’d use the water from the house well as well.”

As children, she and Ginny were forbidden to drink from the pump “because it was mainly rainwater from the farmhouse roof. And any groundwater that might have seeped in.”

She remembers the two of them washing their mud-caked feet at the pump. Having dirty feet was hardly unusual for two small girls on a farm, whose daily playtime included forays in the barns, climbing trees, running through the picturesque ravine behind the farm, and tending to the usual array of farm pets and other animals.

Brenda was an only child, so the opportunity to spend a day at the farm with Ginny was something she looked forward to. Later, as the girls grew older, their grandmother, Alice May Perkins, assigned them the inevitable chores that needed to be done, if only to keep the pair out of mischief.

The two girls regarded one another as the sister neither had.

“I couldn’t wait to get there. We had the entire farm to ourselves mostly. We fed the chickens, watered the horses, tending grandmother’s garden. And, yes, we got into trouble occasionally.”

Like the time Brenda locked Ginny inside an outhouse, a two-holer used for the fruit pickers, during one of their not infrequent childhood spats.

“My mother had knitted me a pair of red woolen mittens and Ginny threw them down the hole. So I locked her in from the outside.”

And then she forgot about her. Fortunately, noticing Brenda playing quietly alone about an hour or so later, their grandmother inquired about Ginny’s whereabouts and Brenda had a sudden epiphany.

Or the time the two girls daubed green house paint onto their grandfather’s new black DeSoto automobile, using sticks for brushes.

“Grandpa had been painting the farmhouse trim park-bench green and he must have left the open can of paint unattended. We would hear about the incident for years to come.”

As they got older, the girls would help with the annual harvest of sweet cherries, raspberries and varieties of apples and pears that Perkins grew on the farm, selling some of the fruit at a small wooden stall along the highway. Occasionally, some of the Perkins’ family of seven children, as well as the younger generation like Brenda, Ginny and a host of other grandchildren, would partake in the tree pruning, fruit spraying and the harvest itself, work that needed to be done.

“That’s the way it was then,” she remembers. “The way we were. You were family and you helped out.”

Work was forgotten on Christmas Day, however, when the family all came together, some arriving early for “a basic Christmas dinner,” usually a turkey prepared by Sauer’s grandmother, while others sauntered in later, after dinner, and after their own family obligations had been addressed.

“We were all just happy to be there, to talk to everyone. We filled every room. There was always something going on — in the kitchen, the dining room, whether it was music, cards being played, drinking, smoking. We were together as a family and just enjoying one another.

“No one just came in as a guest. We all pitched in. And there was always laughter and music. Everyone joined in and sang Christmas songs. It was a happy occasion. The house was just alive.”

One particular Christmas evening, she was surprised to see her grandfather come into the dining room with a violin, something she had never seen him with before, and join in on carols with his son Coleman (known as Bud) on guitar and his daughter Bette on piano.

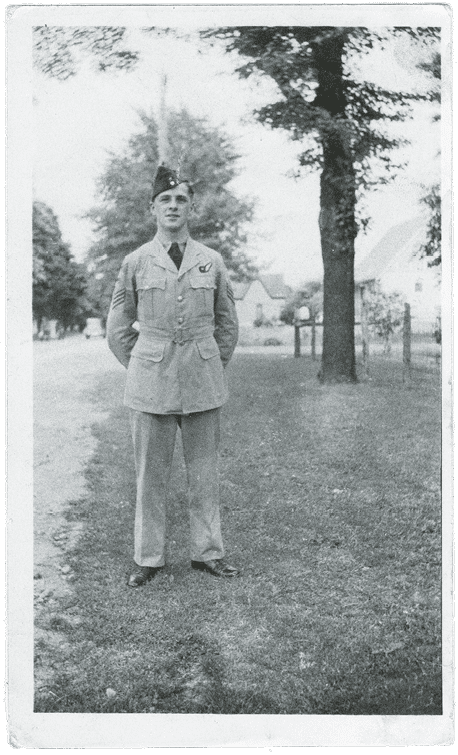

It was 1945 or 1946. Brenda was a young child. The Second World War was over and three of Perkins’ sons — Bud, Mickey and Hollis (called Cy) — were home from overseas.

“It was just that one time. He went upstairs and brought down this violin from his room. I never knew my grandfather played the violin until that Christmas . . . and I never heard him play it again.”

Bud, who had been in the Air Force and survived 33 bombing missions over Europe, was to perish a few years later at the age of 30 in a civilian air crash. Bette contracted multiple sclerosis in her early 20s and eventually succumbed to the disease.

For the younger children, there were always chocolates and soft drinks, and a well-stocked supply of cigarettes and adult refreshments for the others, even though Alice May Perkins frowned on drinking on Christmas Day. And especially so in her kitchen where card games — euchre, poker, and something Brenda remembers as “tinkle-tinkle” — were taking place once the dishes had been cleared.

Tinkle-tinkle was so named for the sound of loose gambling change landing in a saucer placed in the centre of the kitchen table.

“My grandmother, who wasn’t all that happy about the drinking and gambling, would simply absorb herself in her favourite Christmas pastime,” Brenda recalls, namely munching on chocolate-covered ginger from Laura Secord and dipping into a large jar of pickled pig’s feet. “She just sat there by herself, away from the noise and singing. She was in heaven.”

“One Christmas there were five babies a year-and-under there. The women would usually be in the front living room, the men in the kitchen playing cards, always in the kitchen. Ginny and I would pull up a chair and just watch them. Everyone was happy.”

There comes a time, though, when everything unalterably changes.

In the 1970s, John Perkins fell off a ladder in his orchard, punctured a lung and suffered a stroke after being administered aspirin, dying within the year. Alice May Perkins, her daughter Bette and son Hollis soon followed, all passing away a short while later.

The farm was sold and the household goods and farm implements auctioned off, embittering some family members who felt they should have had a role to play in the dispersal of the property. Needless to say, the deaths and sale of the farm brought an end to what had been a long family tradition.

“Everything seemed to change so quickly. Those family gatherings just ceased to exist for many of us. It was sad in a way.”

Still, the memories of those Christmas days and evenings linger in her mind and Brenda can’t ignore them.

Not all memories fade. Some can be stirred by the sight of a simple water pump. ◆

Bill Eluchok, a teenager then, spent part of July 1955 picking cherries at an orchard across from the Perkins farm.