Our family’s plant-based diet is having positive impacts. Health-wise, it’s easier to maintain a proper weight which staves off the disorders that come with carrying extra poundage, tests have shown it’s lowering our LDL cholesterol and blood pressure, and we feel a bit better knowing there may be fewer cattle spewing methane into the air because of our dietary choices.

But personally, I’m plant-based not plant-infatuated or plant-monogamous. And ultimately my diet choices revolve around successfully getting up Saylor’s Hill for yet another year on my bicycle early each spring.

Research tells me that animal-based iron (heme) is more easily absorbed by the body than plant based (non-heme) iron, and iron carries those tiny oxygen molecules my thighs so love when I’m halfway up Saylor’s or 70 kilometres into a windy bike ride.

Somewhere along the line I’ve also figured out that if horses have to eat two percent of their body weight in grass and hay per day to maintain their muscle strength, that translates into a lot of kale and Brussels sprouts for me each day, and a clean, but very busy, digestive system. This has led me to learn more about my digestive system, and its most important part, the gut microbiome.

We’ve all known there was something special going on behind our navels since Danone, a giant multinational food corporation, introduced Actimel, a drinkable probiotic yogurt, in Belgium in 1994. It’s marketed as DanActive in North America. Today Danone sells more than one million bottles a day of Actimel in Europe alone, so clearly many people believe in trying to maintain a healthy gut.

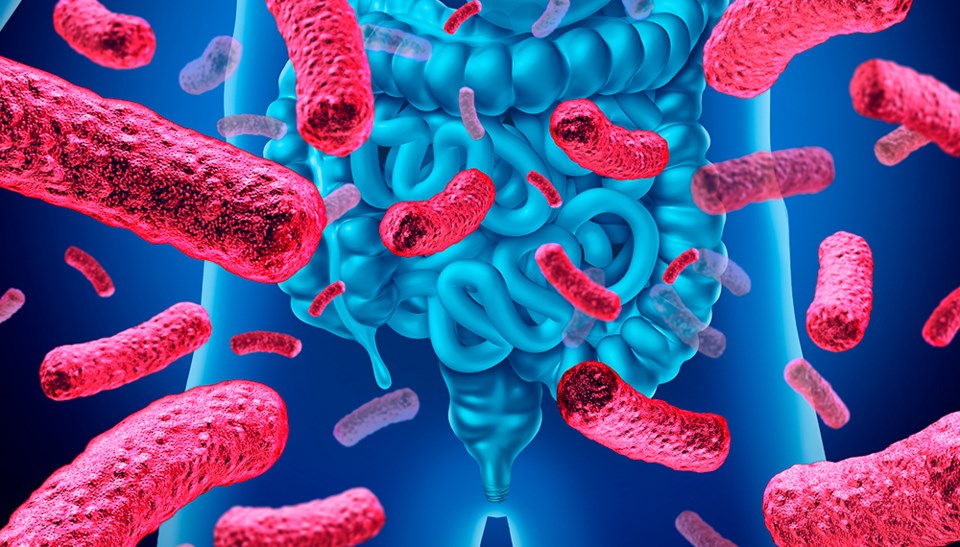

What is your gut microbiome? A biome is defined by Science World Publishing as, “A geoclimatic zone that is identifiable on a global scale and includes things such as plants and animals.” A gut microbiome shrinks the global scale to fit into our bodies, hence micro, and contains trillions of microorganisms (also referred to as microbiota or simply microbes) including thousands of types of bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses. Most of these microorganisms are found in our small and large intestines, but there is evidence that some can migrate to other areas of the body.

This mix contains helpful and potentially harmful microbes which generally co-exist in harmony to provide healthy gut function. Most are in fact symbiotic, in that co-existence benefits the both microbe and our bodies. In a healthy body these symbiotic microbiota keep the disease-promoting microbes in check. If, however, the balance is upset and pathogenic microbes begin to flourish, dysbiosis sets in making our bodies susceptible to illness such as cramping, constipation, indigestion, bloating and diarrhea. Left untreated, more serious disease may result.

Each of us develops a unique gut microbiome, or bacterial footprint. In the womb our microbiome is determined by our inherited DNA. Our journey through the birth canal expands our microbiota mix, as does nurturing breast milk packed with healthy bacteria. Our environment, behaviours and most importantly diet continue to alter our gut microbiome as we grow. Infections, illnesses, stress and the extended use of antibiotics or antibacterial medications are disrupters of our gut biomes.

This mix contains helpful and potentially harmful microbes which generally co-exist in harmony to provide healthy gut function

Why is our gut microbiome important? Many scientists and medical professionals consider the gut microbiome to be a support organ — it is that important to our health. The Harvard Chan School of Public Health puts it this way, “Microbiota stimulate the immune system, break down potentially toxic food compounds, and synthesize certain vitamins and amino acids, including the B vitamins and vitamin K.” A healthy gut, performing necessary digestive and regulatory functions, is essential to keep us operating at our best.

Most sugars are absorbed rapidly in the upper small intestine, but more complex fibre and starches need the microbiota enzymes living in the large intestine to be digested. Indigestible fibres and non-digestible carbohydrates ferment in the gut, producing short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), some of which affect our lipids and hence protein metabolism in skeletal muscle. Since skeletal muscle is the largest of our organs, microbiota indirectly affect our complete body metabolism, which controls the relative amounts of energy our bodies store to support new cell and tissue growth or burn to provide heat and motion.

Our gut microbiome also protects us from disease and inflammation in other ways. The anaerobic bacteria of the large intestine (colon) protects the mucous membranes of the gut itself from harmful antimicrobial proteins which cause it to leak, allowing small particles of food and bacteria into our blood. Our immune system sees these infiltrators as harmful and creates beneficial acute inflammation to protect us. Left untreated, the result is chronic inflammation, a trigger for multiple diseases and mental health issues including cancer, heart disease, asthma, and Alzheimer’s depending on which organs are affected.

How do you control your gut microbiome? Australia’s Deakin University Research Centre states simply, “In fact, diet is the most important modifiable factor affecting the composition of bacteria living in our gut.”

Science is just beginning to understand gut health, and what makes up a “healthy” gut. General properties are known, but quantifying the perfect mix of microbiota for each of us is a long way off. Most experts believe that having as many different, diverse types of bacteria in our intestinal tract is beneficial to good digestion, including nutrient production, and offers the best resistance to pathogens.

Foods which contain natural living probiotics, the bacteria which promote fermentation in various foods, are the best source of gut-friendly microbiota.

The most popular such food in North America is yogurt, produced from milk that has been fermented by naturally occurring lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria. Kefir, made by adding cultures of lactic acid bacteria and yeast to cow’s or goat’s milk is considered more potent because it contains significantly more diverse strains of bacteria than yogurt.

Other fermented foods from around the world are good sources of probiotics.

Sauerkraut and kimchi, fermented shredded cabbage, also contain Vitamin C and K, antioxidants lutein and zeaxanthin for eye health, and iron and potassium.

Tempeh, miso, and natto, all fermented soy products, and good old-fashioned pickles—fermented cucumbers—contain high levels of beneficial probiotics.

It should be noted that pasteurization of these products will kill their beneficial probiotic bacteria, so check the labels.

Live probiotic supplements are also available as pills, although many question their necessity and effectiveness for healthy adults who maintain a gut-friendly diet. Dr. Alan Walker, Professor of Nutrition at Harvard Medical School, says, “Probiotic supplements can be most effective at both ends of the age spectrum, because that’s when your microbes aren’t as robust as they normally are.” He also suggests supplements after the use of antibiotics, or when suffering from other intestinal imbalances.

Reducing our intake of medicinal antibiotics when possible is beneficial to gut health. So is consuming fewer broad-spectrum antibiotics via foods such as chicken, eggs, meat, farmed fish and dairy in which antibiotics were part of their production or food supply.

Adequate sleep, regular exercise and limiting stress can also ensure a healthy gut. Wonder if that includes stressing over what to eat? ◆