There I sat in my clerical collar and black suit, an Anglican priest confident in my political and social awareness and in that of my church. In quiet yet confident tones the Indigenous leader who was speaking that day told a personal story. He loved his grandpa very much, he told us, but never understood why this learned, kind man would never hug him. One day, when grandpa was very elderly and our speaker was an adult, he asked him why. “I could never have told you this before”, said grandpa, “but when I was a child in a residential school, a hug meant only one thing. It meant that I was going to be raped.” Pause. “That’s why I could never hug you, that’s why.” I’m sure I wasn’t alone in feeling tears come to my eyes.

But tears have never been enough, and the obscenity of the residential school system has taken far too long to be exposed. That’s why Indigenous delegates were in Rome two weeks ago to meet with the Pope, to ask for an apology for what Roman Catholic priests and teachers did between the 1840s and the 1990s, when some 150,000 First Nations children were taken from their families in a mass effort to convert them, “make them white” and, “take the Indian out of the Indian.” The concept was hideous, and the application worse. There was physical and sexual abuse, lack of medical care, and sheer cruelty.

On the final day of the visit, Francis delivered words that, frankly, the group didn’t think would be forthcoming. “I also feel shame ... sorrow and shame for the role that a number of Catholics, particularly those with educational responsibilities, have had in all these things that wounded you, and the abuses you suffered and the lack of respect shown for your identity, your culture and even your spiritual values,” he said. “For the deplorable conduct of these members of the Catholic Church, I ask for God's forgiveness and I want to say to you with all my heart, I am very sorry. And I join my brothers, the Canadian bishops, in asking your pardon.”

I ask for God's forgiveness and I want to say to you with all my heart, I am very sorry

It’s taken such a long time, but means so very much.

Last year alone, the remains of hundreds of Indigenous children, some as young as three years old, were discovered. They were anonymous, and their bodies were given no respect or dignity. Horror stories abound, all part of what is this country’s birth defect: its cultural genocide and physical destruction of people native to the land.

The Roman Catholic Church isn’t the only culprit of course, but other religious institutions, and secular bodies, acknowledged their crimes in the 1980s. To make matters worse, the Catholic Church ran most of these schools, and while there had been vague statements of regret and sympathy, it took intense public pressure and even threats regarding the funding of Catholic schools and the removal of tax-free status for churches, for Canadian bishops to apologize last year. There were also examples of denial, arguments that it wasn’t as bad as survivors claimed, or—quite incredibly— that while abuse was regrettable, at least these children were brought “the light of Christ.”

The Vatican hasn’t been as crass but nevertheless still refuses to provide documents that would reveal details and culprits. Under the 2005 Indian Residential Schools Settlement, the Canadian church also promised at least $25 million for Indigenous communities, but only a fraction of that amount was ever given. The church argued that it couldn’t raise the money, but did find large amounts to restore old churches, including the purchase of elaborate furniture and stained glass. The insulting juxtaposition wasn’t lost on survivors.

The delegation also requested that Rome return artifacts from its various museums and collections, and open up its archives so that the residential school system can be fully researched. In other words, this is in many ways the beginning of a process, and one that could take many years.

One of those in Rome last week was Tanya Talaga, a highly respected author and journalist of Anishinaabe heritage. She tweeted this: “Today, I visited Anima Mundi, part of the Vatican Museum with Indigenous ‘artifacts’ kept in the Church’s private collection. There is an ‘Ontario’ pipe stove from the 18th century, Haida Gwaii masks from the 18th century, much more. I photographed them and was asked to leave.”

Yes, there is still far more to do. ◆

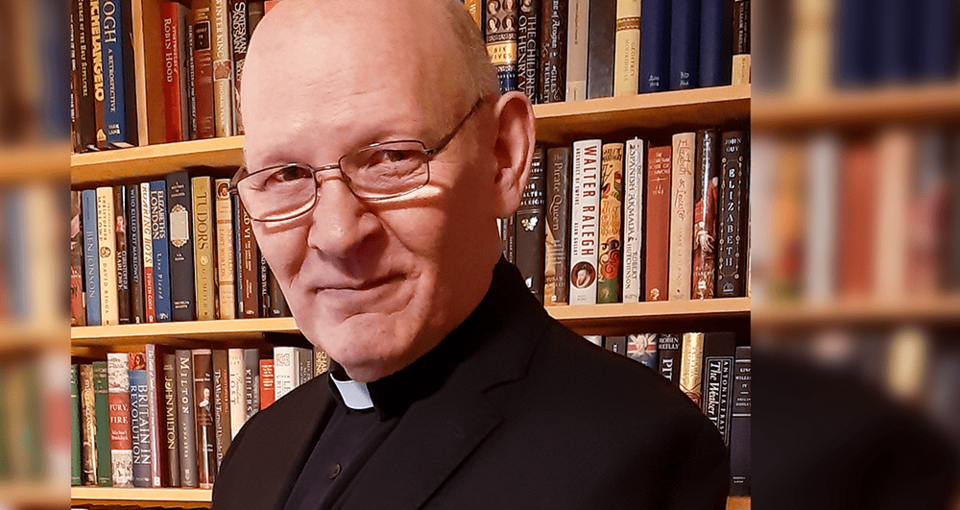

Rev. Michael Coren is an award-winning Toronto-based columnist and author of 18 books, appears regularly on TV and radio, and is also an Anglican priest.