Beware the guy with cauliflower ears

Think being a cop is easy? Sunshine List paycheques, copious doughnuts, and cushy assignments in crowd control at Blue Jays games?

I’ve got breaking news for you. The job is stressful, and often requires officers to make split-second decisions in uncertain situations. Unholster your firearm when you should have drawn your baton or pepper spray instead, and you’ll get lawsuits, SIU interrogations, and a desk assignment. On the flip side, pull that 40-calibre Glock too late and you could end up in the ICU, or toe-tagged in the morgue.

At the invitation of the Niagara Regional Police Service (NRPS), I spent last Monday morning in a crash course in policing at their training facility located at Niagara College in Welland. It was the third such media-focused police training day offered by the NRPS as part of the annual Police Week, and boiled down to a heavily condensed version of the 13-week Ontario Police College training program in Aylmer—the Coles Notes bullet points, so to speak—minus (thankfully) the hefty fitness component.

Four other intrepid journalists — Dave Johnson from the Niagara dailies, Evan Saunders from the Lake Report in NOTL, Mike Balsom from YourTV/Cogeco (and occasional contributor to the Voice), and Stephen Murdoch, VP for Public Relations at Enterprise Canada — joined me in the demonstration, intended to give both the media and the public insight as to how the NRPS prepares their officers to protect and serve the community.

Topics discussed, demonstrated, and replicated included use of force protocols, defensive tactics, firearms and conducted energy weapons (aka Tasers), and situational police scenarios that subjected the participants to physical and mental stress.

NRPS Chief Bryan MacCulloch offered greetings, noting that “safe communities really can't happen without partnerships. Our officers are experiencing so many challenges nowadays on the front line: mental health issues, drug addiction, homelessness, poverty. We feel that the media plays a huge part in helping us get the story out to our community about what's going on in the policing world.”

The Chief expressed a prophetic warning.

“You'll see that when you're involved in some of the scenarios, they happen very quickly,” he said. “We're not here to trick you. The situations that you're going to face are real-life scenarios that our officers have experienced, which we’ve incorporated into our training.”

The situations that you're going to face are real-life scenarios that our officers have experienced, which we’ve incorporated into our training

NRPS Media Specialist Constable Phil Gavin underscored the Chief’s message.

“This is a volunteer experience,” said Gavin. “There's no hero cookie involved. If you do not feel comfortable with anything you're asked to do, just say ‘stop.’”

MacCulloch said that the NRPS brass recently reported annual use-of-force statistics to its overseeing body, the Police Services Board.

“In 2021, out of literally hundreds of thousands of interactions where our officers engaged with members of the public, there were only 186 incidents that required the filing of a use of force report,” he said. “We’re talking about a very small number of incidents, and I think that's really a testament to the training that our officers received at the Ontario Police College, reinforced by our fabulous instructors here at our NRPS training centre.”

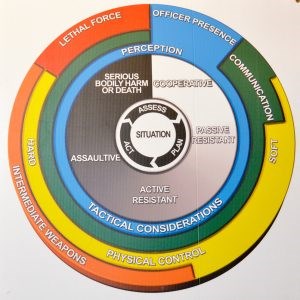

Constable Andrew Watson, one of the instructors, provided a lecture on the NRPS’ use-of-force model, a wheel-shaped graphic representation of the elements involved in the process by which cops assess a situation, and respond in an appropriate manner.

“What’s the individual’s behaviour?,” asked Watson. “Is he cooperative, passively resistant, actively resistant, assaultive, or does he possess a lethal weapon that potentially creates a life-or-death situation?”

An officer’s perceptions mesh with tactical considerations, such as the environment (confined or open area, bright daylight or poorly lit alley at night), the number of subjects, knowledge of the subject (criminal history), possible subject abilities regarding physical violence based on size and musculature, and what Watson refers to as “time and distance.”

“We tend to deal with some of the same people over and over again,” said Watson. “If a guy is known to like to fight with the police, that's going to affect how close I get to him. Time and distance allows us to properly assess the situation. Communication is the biggest tool we have, better than anything on our service belts. Our job is to de-escalate a situation, and the best way to do that is with great communication.”

Every situation is different. Perhaps a police dispatcher provides a description of a suspect, related by a citizen, along with a criminal history check. It could be a routine traffic stop for a broken taillight. But what if the vehicle was reported stolen, or the registered owner has multiple weapons violations?

“What are his hands doing?,” asked Watson. Are his fists clenched? Is he reaching for something? Does he have cauliflower ears?”

Guys who are regular brawlers, or training in boxing, wrestling, or the martial arts, often bear scars and, yep, an ear deformity called cauliflower ear, caused by blunt force trauma or injury. It’s a warning that this bloke might have no trouble with mixing it up a bit.

“Obviously, if a guy is standing there with his fists up and verbally threatening you, there’s a good chance things are going to get ugly real fast. In policing, we call that a ‘clue,’” said Watson with a sly grin. “If he’s gritting his teeth, and has that eerie 1000-yard stare, it's a sign that maybe I should back off and reassess the situation.”

Watson said that it’s not unusual for some scrappers to size up an officer’s duty belt.

“People that want to attack us will stare at our Taser, our pistol, our baton,” he said. “That’s another clue that things could deteriorate rapidly.”

People that want to attack us will stare at our Taser, our pistol, our baton

Constable Chad Davidson led the media recruits through soft and hard physical control measures, using pressure points, kicks, and punches. Intermediate weapons such as OC (oleoresin capsicum) pepper spray, and the 21-inch telescopic metal baton, were also demonstrated.

“We use the baton in two ways, either in a striking fashion, or in a ‘soft mode’ application, to essentially pry a resistant person’s arm free,” he said. “We teach officers a pattern of strikes not involving the head, neck, joints, or back. We're striking major muscle mass against a person displaying an assaultive behaviour.”

In 2020, batons were used only twice by NRPS officers, in a soft application. Officers drew their pistols 66 times, discharging them 12 times. They are trained to fire their weapon until the threat is neutralized.

Constable Rich Vujasic provided the skinny on use of the Taser, a reliable, non-lethal tool which fires two darts about a foot apart attached to the device by 25 feet of wire, conveying an electrical current which usually renders the target immobile.

“I want to create MNI, or muscle-neural incapacitation,” said Vujasic, who said that the darts work on individuals wearing heavy winter clothing, and that the main body mass (torso) is always the target.

The Taser is holstered on the left side of the officer’s duty belt, away from the Glock handgun, which is on the right. The Taser requires a cross-draw by a right-handed officer, thus eliminating (with training) confusion with the service pistol, which is for lethal purposes only.

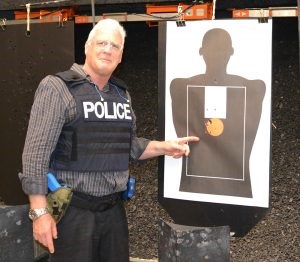

Firearms instructor Constable Brittany Wright was up next, and explained (amidst groans of disappointment from the assembled writers) that, due to a ventilation issue, live ammunition would not be used. (You don’t want to be inhaling lead residue from a fired round.) Instead, we would be employing a lower-velocity projectile in the Glocks called Symunition, which offers no recoil, but still goes “bang” and strikes with accuracy over short distances.

Wright explained the concept of muzzle integrity, which is a fancy way of saying keep the pointy-end directed towards the target. We were each assigned an officer to closely supervise our pistol use.

“Leave it in your holster until you're given instructions do to otherwise,” stressed Wright, appearing, for some undetermined reason, to be looking directly at me as she issued the warning. She explained universal cover mode, which means you don't put your finger on the trigger until you have drawn the weapon and made the conscious decision to fire.

“We're shooting at the upper thoracic area, the torso, where there are a lot of organs,” she said, “which causes rapid incapacitation. We're not shooting to kill anybody, we are shooting to stop the threat. Once we have done that, we secure the scene, and immediately render first aid to that person.”

We were taught pistol grip, stance, racking the slide, target acquisition, trigger control, and moving from the tuck position to “punching out” with the pistol.

Our paper targets were set at a distance of only 10 feet, which might seem very close. But they are obscured until they abruptly turned to face us, at which point we attempted to quickly unholster the pistol, assume our grip and stance, acquire the orange square in the centre of the target, and fire off one round in two seconds. Then two shots in three seconds. Then one shot in one second. The adrenaline was pumping.

If your idea of pistol shooting is James Bond dropping some miscreant at 50 yards with his puny Walther PPK, let me enlighten you. That’s pure Hollywood. It just doesn’t happen in real life. Shooting a handgun with precision is hard, even at close range, due to the short sighting radius (the distance between the front blade sight and the rear notch sight.) Rifles have a longer sighting radius, and that’s why they have greater accuracy.

We're not shooting to kill anybody, we are shooting to stop the threat

I managed mostly hits in the fluorescent square, with only two straying high and to the left (not unlike my tee shot on the golf course.) At greater distances, I would no doubt have missed the target completely. Regular practice makes the process instinctive, we are told.

The grand finale was the much-anticipated series of real-life scenarios.

Dave from the dailies assumed the role of an officer stopping a vehicle on a darkened roadway, police cruiser lights flashing as he exited the car with his flashlight. Two guys got out of the van in a belligerent state. After a brief exchange of words, and commands by Dave to step away from the vehicle, the van driver retreated back inside the car, emerging with something in his hand.

Dailies Dave drew his Taser, but in the heat of the moment, neglected to turn it on. Luckily for Dave, the man turned out to be holding a cellphone and not a weapon.

“If it's out, it should be on,” instructed Sergeant Matt Whiteley, referring to the police protocol with the Taser.

Mike from Cogeco was next, informed that Best Buy had reported a shoplifter running from the store, wearing a white hockey jersey and dark pants, and carrying a backpack. Mike cornered him in a poorly-lit room.

“You're way too close, dude, I’m telling you right now,” said the suspect (one of the police instructors assuming the role), who proceeded to extract a cellphone and laptop computer from the backpack.

Ignoring Mike’s repeated commands to drop the backpack, the perp snarled, “I've got something else for you,” and pulled a handgun from the pack.

“Bang, bang, bang, bang.”

Mike, with that deer-in-the-headlights look in his eyes, froze, and ended up shot before he could react with his own firearm.

One of my scenarios was played out using the electronic judgment training system, or simulator, that interacted with the screen through an infrared connection to my service belt weapons, which was read by the cameras on top of the projector.

I was told that there had been a break-in at a factory, and I was to investigate. As I scanned the room with my flashlight, a man entered through a door and stood in front of an enclosed counter.

“Get on the ground!” I told the guy, in my most assertive voice.

“Hey, man, what’s going on? I work here,” the guy responded.

I repeated my command twice, and then told him that if he didn’t step back from the counter and get on the ground, I was going to tase him.

I could feel my pulse quicken. Tiny beads of sweat gathered on my brow. My palms were wet as I drew my Taser.

At that instant, the guy reached under the counter, and produced a handgun.

“Bang!”

An opening for a contributing editor just opened up at the Voice of Pelham.

Another simulated scenario involved a suicidal man with a handgun, talking to his girlfriend on the phone, who failed to heed Evan from the Lake Report’s call to drop his weapon. The despondent man ended up pointing his gun at the wannabe officer, seemingly a wish for “death by cop.” Evan paused, perplexed.

The consensus of the officers was that, at that point, lethal force would be a very real option for an officer.

My favorite simulation was of a traffic stop involving a shapely young woman, who exited her vehicle wearing a revealing halter top and cutoff shorts. It took us (well, me specifically) about ten seconds before I identified a handgun hanging from the door panel. Hey, I was distracted!

Back in the briefing room, we discussed the scenarios, and were reminded that the police response must be reasonable under the circumstances. You can’t unholster your sidearm if the guy is just giving you attitude. If he has a rap sheet for violence and comes at you with a Louisville Slugger, well, that changes things. But cops will still pull their Taser before their Glock except in extreme situations.

Asked about his best moments as a police officer, Constable Davidson expressed his fond memories of working in Niagara high schools as a resource officer.

“I’ve actually had a recruit who's going to the Police College, who remembers me as a resource officer when they were in Grade 10,” he said. “We had a great conversation about policing. And a young lady, that I actually arrested on one occasion, invited me to her high school graduation ceremony, saying that I had a positive impact on her life. ‘Without you, I probably wouldn't be graduating,’ she told me. That was, for me, a wonderful moment.”

One officer shared a “lived experience,” and referenced his involvement in a police shooting four years ago of a knife-wielding assailant, which exacted a toll not just on the person who was shot, but on the mental state of the officers who confronted the attacker.

Bottom line: cops are ordinary people doing an extraordinary job. They want to go home to their spouse and kids at the end of the shift, just like your average teacher, florist, restaurateur, or backhoe operator. Unlike these other occupations, however, cops often carry a heavy psychological burden. For most police officers, shooting someone would be the worst day of their life.

They are public servants, who endure more than their fair share of abuse, and need to make split-second decisions under trying conditions.

They are well-trained and, yes, well-paid. And they work hard to be well-respected.

Remember that next time you’re inconveniently pulled over for speeding, and are politely requested to produce your license and registration.

I’ve got to admit, though, the thrill-seeking side of this 60-something scribbler enjoyed the whole experience. Which prompts my question, Chief MacCulloch, will you be taking on any new recruits who are senior citizens? ◆