When my daughter Lucy was a tiny child, just turned four years old, I took her to see The Nutcracker, in Toronto, that annual event of pristine Christmas escapism. There she was, in her party dress, with a smile and enthusiastic anticipation, sitting on her booster seat and leaning in as if magnetized to the ballet, its music, and its fantasy. Then the music ended, the audience applauded, and we left.

At which point she began to cry. The tears bisected her miniature cheeks, and she was nothing but weeping and sorrow, and it was as if my life was collapsing before me. Why Lucy, why? She had seemed so exquisitely happy. “Because,” she said, in between gulps for air, “because it’s stopped and it’s finished”—more agonizing gulps—“and I don’t want the magic to be over. I don’t want the magic to end.” Now it was my turn to feel tearful. But I managed to reply: “Darling, I promise you, I promise you with all I have, that the magic will never end.”

It was an enormous promise to make, the earnest, naive kind that parents use which, in the eyes of the child, only burnish their mythical status. But it’s also the kind that infers a kind of control that parents eventually come to realize they do not have.

Then the child turns into the teenager, who becomes the young woman, now a young mum.

I gave a speech at her wedding, and there were no grotesque clichés—no “I’m not losing a daughter but gaining a son” stuff. I tried to to tell her, in the simplest of terms, that I loved her. But that phrase seems weak. What I feel is more complex than that. After all, the common idea of a parent’s love for a child feels superior, protective, even condescending, when really, a parent’s relationship with a child is symbiotic.

Any mother or father who assumes that they are the exclusive guide and guard of their child should think again. Children make the world appear much more dangerous and vulnerable, but also far more exciting and new again. They teach just as much as we do—and in Lucy’s case, I think I’ve more often been the student.

So instead of “I love you,” I told her that I’ve often failed. Not through lack of effort, and often due to too much rather than too little concern, but that I got it wrong more times than I can count. That contrary to those syrup-soaked greeting cards, genuine love doesn’t mean never having to say you’re sorry—but rather saying it almost all of the time.

That contrary to those syrup-soaked greeting cards, genuine love doesn’t mean never having to say you’re sorry—but rather saying it almost all of the time

I told her that a father’s love for a daughter means knowing when one is wrong, trying to repair damage done, empathizing with what can seem bewildering and even intimidating, letting go instead of holding on, and seeing the autonomous splendour in a child instead of trying to glorify a version of the parent. Parental love is rejoicing in the shock of the new, and singing the metaphorical songs and poetry of a new generation that does not belong to us.

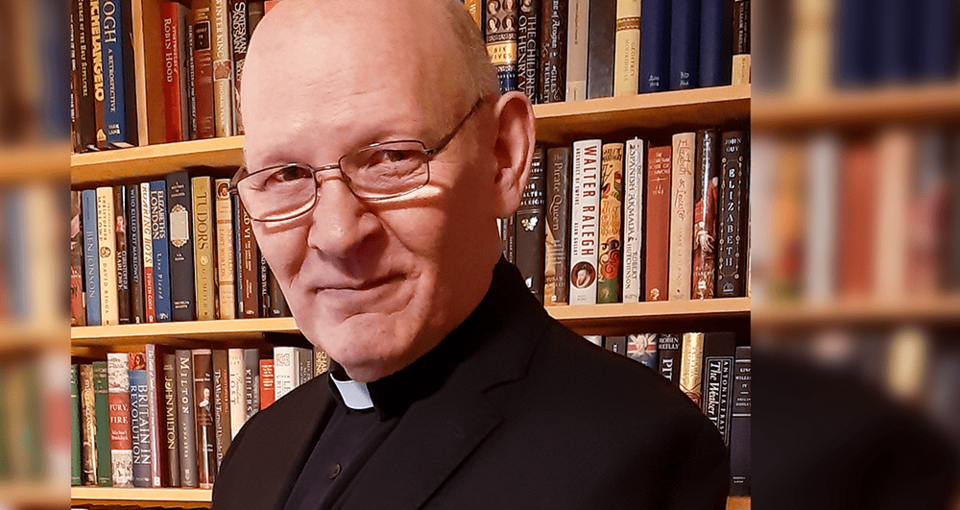

My daughter changed me. Her attitudes and relationships liberated me, and frankly her wisdom shamed me. When eight years ago I embraced equal marriage, social liberalism, and what some see as a revolutionary form of Christianity, Lucy, who had long rejected organized religion, said to me: “Dad, I would never have asked you to do this, but I am so, so glad that you have. I am so happy.” I went to my study and I wept.

My parents are gone now, and how I wish they could see their precious granddaughter now. But the ages of humanity have to pass, as they always have, and always should. Lucy, I know that I too will not be with you forever, and that hurts me and I know hurts you. I have done what I could and tried my inadequate best. But please know, my darling, that I am more proud of you than I could ever say, and that what I told you more than two decades ago still holds true. Not because of anything I could ever do, but because as long as you want it to be so, the magic never ends. The music may stop, the dance will finish, and the curtains may draw, but the magic never ends.

That’s something I hope you tell your baby boy, and he — God willing — his children too. The magic never ends.