Political conservatism has come a long way. But in the spirit of the word and the ideology, that doesn’t signify progress. In fact, the decline and decay of the organized conservative movement in the democratic world is one of the most worrying phenomena of contemporary politics. Worrying because unlike the extremes of right and left, parliamentary conservatism is established, respected, and often in government and power.

As a philosophy, it’s always been vague by its nature, and in its pragmatism almost not a philosophy at all. We can look to the Irish MP and author Edmund Burke or the Tory movers and shakers of the 19th century, but the context then was profoundly different. The conservative parties of Canada and Britain—they’ve usually been similar in outlook and policy—were until the 1970s paternalistic, moderate, and supportive of qualified change and reform, and consensus governance. Canada’s linguistic and geographical divisions added other spices to the menu but the fundamentals remained. The centre was occupied by all of the major parties.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s this all began to change, with a new generation of young conservatives anxious to intellectualize the movement, and obviously tired of being seen as the unthinking voters. I can remember my university days back then when conservative students would carry copies of Austrian economist and philosopher Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom under their arms, would discuss the market economics of Milton Friedman, and hold seminars to consider libertarianism.

This was the era of Ronald Reagan, Brian Mulroney, and especially Margaret Thatcher. The British leader transformed her party into something entirely different from the red Tory past, and directly attacked the notion that it was the duty of government to care about the weakest. “There's no such thing as society”, she declared. “There are individual men and women and there are families.”

That view, the rejection of the alleged “nanny state,” the celebration of financial success if not downright greed, the emphasis on ostensible personal liberty, all mingled with a nostalgia for an imagined past, and a sympathy for if not complete acceptance of social conservatism, influenced right-wingers the world over. Which in Canada meant Stephen Harper and the politician and journalists around him.

Then came the disappearance of the federal Progressive Conservative Party and most of that for which it stood. The timing here is vitally significant. As obnoxious as much of what the Thatcher-style of politics was, it was at least rooted in a consistent worldview. But foreign wars, the triumph of unanchored social media, the decline of industry, and the evaporation of what many saw as traditional values created a vacuum on the right. It was filled by populism, conspiracy theories, utter hatred for mainstream media, and ultimately by Donald Trump. He changed everything, because it was seen that someone so apparently absurd, so bombastic and chauvinistic, and so linked to the new right could win at the very highest level.

Former Tory leaders are dismissed with contempt—solidly conservative but responsible politicians such as Erin O’Toole are humiliated and chased out of office, and media platforms that deal in raw sensationalism or downright nonsense grip the conservative rank-and-file in a vice of hysteria and paranoia.

We see in the race for leadership of the Conservative Party a surreal circus, with various candidates trying to outdo each other in their commitment to extremism. The party of Kim Campbell and Joe Clark has become the venue for talk of Bitcoin, support for the occupation of Ottawa by fanatics, and denial of science and fact.

Informed and mature conservative activists and journalists who criticize any of this are insulted as sellouts and “liberals,” and those who were once considered pariahs in Canadian politics are given room to speak and have influence. Tails wag dogs, and anybody who aspires to lead has to make sure to be ideologically pure, even if it means encouraging the sewers to breathe.

There has been talk of the Conservative Party splitting after the current leadership campaign but that’s possibly a misnomer. A group of people leaving a major party is less or a split than a splinter. As troubling as it is, there’s no restoring Canadian conservatism to what it was, as most of the membership has long moved on. The only question is whether the electorate is willing to support them when it comes to voting. For those who assume that Canadians would never do so, I’m afraid I don’t share your sense of optimism.

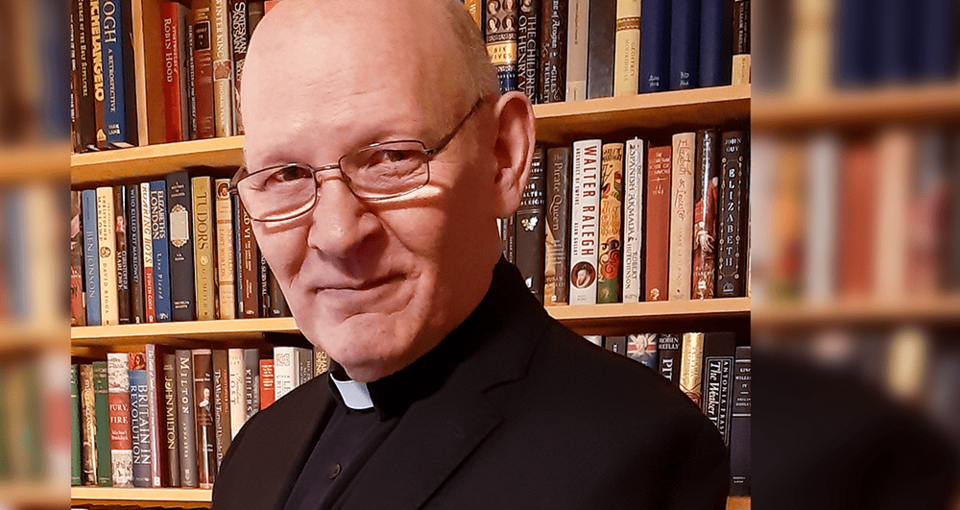

Rev. Michael Coren is an award-winning Toronto-based columnist and author of 18 books, appears regularly on TV and radio, and is also an Anglican priest.