The new Amazon Prime blockbuster, The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, which will cost in the region of $200 million dollars per season, making it the most expensive television series ever made, has just begun. Set thousands of years before J. R. R. Tolkien’s better-known works, it remains to be seen how loyal this history of Middle-earth will be to the text.

Tolkien was a man of faith but was teasing about the connection between his religion and his writing. While he described The Lord of the Rings as, “a fundamentally religious and Catholic work,” he also stated in an interview that, “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence.” That was one of the reasons why he was so critical of Lewis’s Narnia stories.

But themes— yes, allegories — of creation and fall, sacrifice and sin, resurrection and redemption, darkness and light, good and evil, permeate his writing, and it’s almost impossible to conceive of a Tolkien world detached from a Christian foundation. He once wrote to a friend, “I am a Christian, and whatever I write will come from that essential viewpoint.”

Tolkien was three years old when his father died. His mother, a far from prosperous widow in Edwardian England, was a Catholic convert and received generous support from the priests of the Birmingham Oratory. She died when Tolkien was 12, after having given his guardianship to her Oratorian friend Father Francis Morgan. It was Morgan who virtually raised the boy.

From then on there’s no evidence that Tolkien ever particularly wavered, although the same can’t be said of his wife, Edith. She had been raised Anglican, converting to Roman Catholicism three years before the marriage in 1916, largely due to Tolkien’s insistence. She later distanced herself from the Catholic Church and resented her husband taking their children to Mass. While the couple managed to reconcile their differences, Edith would never share her husband’s dedication to Catholicism, and it’s even unlikely that she was a regular churchgoer.

While that may seem entirely manageable today, it must have been deeply painful to Tolkien. In one of his letters he wrote, “The only cure for sagging or fainting faith is Communion. Like the act of Faith it must be continuous and grow by exercise. Seven times a week is more nourishing than seven times at intervals.” And, “Out of the darkness of my life, so much frustrated, I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament.”

There is, clearly, a certain rigidity about all this. Tolkien’s grandson Simon told of attending church with his grandfather in Bournemouth, after the liturgy has changed from Latin to English. Tolkien “obviously didn't agree with this and made all the responses very loudly in Latin while the rest of the congregation answered in English. I found the whole experience quite excruciating, but my grandfather was oblivious. He simply had to do what he believed to be right.”

Yet there is also something timeless, even progressive about the man and his faith

Yet there is also something timeless, even progressive about the man and his faith. His startlingly early awareness of environmental challenges, and demand for responsible dominion over creation. His insistence on the importance of simplicity, and warnings of the dangers of wealth and materialism.

It’s perhaps those qualities that have led to his enduring popularity. One of his earliest dedicated readership bases was within the Hippie movement, a subculture known for rejecting rather than embracing organized faith. And it could be argued that for some — science fiction lovers, progressive rock fans, new age believers, for example— Tolkien has become an alternative to the very orthodox Christianity he so revered.

He was aware of that, and often amazed at some of the letters he received from devotees. But it’s to his credit that this bemused rather than disturbed him. Thing is, his faith informed his personality for the better. There’s an indicative story that’s worth the re-telling.

In 1938, when far too many people, Christians included, were still ambiguous about Hitler’s Germany, a Berlin-based company considered a German translation of The Hobbit. Tolkien told his publisher that he considered Nazi race doctrines to be “wholly pernicious and unscientific.” The German publisher eventually wrote to him, asking for a guarantee of his “Aryan descent.” In his response he dismisses the definition as absurd, and then explains that’s he not Jewish. “I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted people.”

Amazon Prime is here. Have faith.

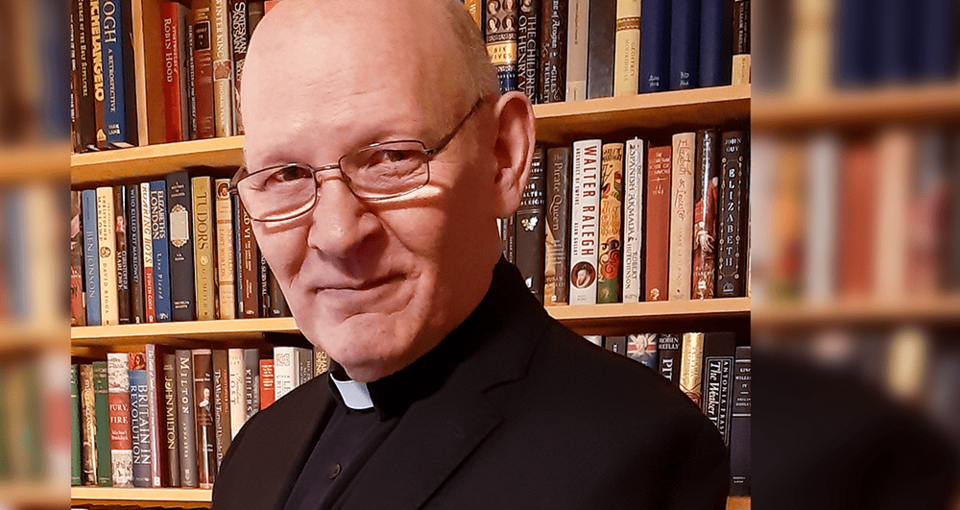

Rev. Michael Coren is an award-winning Toronto-based columnist and author of 18 books, appears regularly on TV and radio, and is also an Anglican priest.